A month or so ago I was talking to an old and close friend and we began discussing reviews of our work. This led to discussing how one reviewer misunderstood my conclusions in The Rabbinic Targum of Lamentations: Vindicating God. Curious to look at it all again, I pulled up the text to my introduction and conclusion (see below). The reviewer, by the way, thought I was espousing the Targumist’s interpretation and explanation of events. I can see how my Conclusion might be misconstrued in such a way, but the Targumist’s view is not my own.

I have noted before the cruel coincidence that I should have spent more than a decade studying how Jews and Christians lament, how we deal with catastrophic loss and suffering. Today happens to be the anniversary of the Sandy Hook tragedy, when a gunman took the lives of 27 individuals, including his mother, before taking his own life. Two weeks from now marks the anniversary of the death of our own son. Loss and suffering is all around.

When I read this now there is little I would change, even after our own personal tragedy. Indeed, Sandy Hook, the Boston Marathon bombing, and the deaths of other young children just in our own region simply underscore the fact that loss is constantly present in this world. We are often sheltered and protected from tragedy, especially in our western cocoon, but it is present nonetheless. I think that is a significant point that I learned during my research that has simply and sadly been affirmed this year, which is that we are too protected.

We are too sheltered and protected from the realities of this life. It is a bit like when we have used too many antibiotics and diseases build up an immunity such that when they do attack we have no defense. Because we, especially as western Christians, no longer tend to experience on a regular basis the kind of loss and suffering that is the true reality of this life we no longer have theologies that can accommodate such loss, we no longer have an understanding of God and his relationship with the world and with his people that can adequately cope with either the person on a shooting rampage or agentless injustice. This is one reason that people like Bart Ehrman leave Christianity at some point. “I realized that I could no longer reconcile the claims of faith with the facts of life.” [mfn]From God’s Problem: How the Bible Fails to Answer Our Most Important Question–Why We Suffer[/mfn]

After Mack died there were some brave enough to ask me if I was losing my faith. I appreciate their honesty and forthrightness (and please, never shy away from asking me or challenging me on anything). When I was doing my research on theodicy I knew then that this it was not just a theoretical exercise and that I too, like Bart, had to wrestle with the fundamental challenge it poses to my belief in God. Just experiencing it myself did not change the facts present in this world. I was able to reply to them honestly that no, I was not losing my faith. But I also responded by rejecting false or partial theologies of suffering and loss. The loss of Mack, as much as it has challenged every aspect of my life, did not bring a new challenge to my faith in God. It is a challenge as old as human experience and one that is answered in Genesis 3.

Which is not to say that it has been easy nor that it has not caused me to go back and revisit my convictions and question my faith.

In fact, I think the greatest fault of western Christianity (and you will note, I am not singling out any one group or denomination, I think this is a problem for all of us living in our comfortable western world, even when it is geographically located in the east, or north, or south) is that fosters the false belief that it is wrong to question your belief, to allow your faith to be challenged. Our faith will be challenged whether we want it to be or not. So we must consider what we believe and why and then be ready, not with pat answers, but to question it again. I believe God is big enough to handle the scrutiny.

Am I losing my faith? No, but I will tell you that my belief in the resurrection has become that much more fervent. How can it not? I long for the day when I will see Mack again, hold him in my arms for a moment or two as he then wiggles away to go run and play soccer. The resurrection is, after all, the lynchpin of Christianity not the belief that bad things won’t happen to people who confess Jesus as Lord. And if it is not true, as Paul wrote, “we are of all people most to be pitied.”

But I remain convinced that it is as true as the reality that we live in a broken world full of suffering. The one does not negate the other, rather it necessitates it.

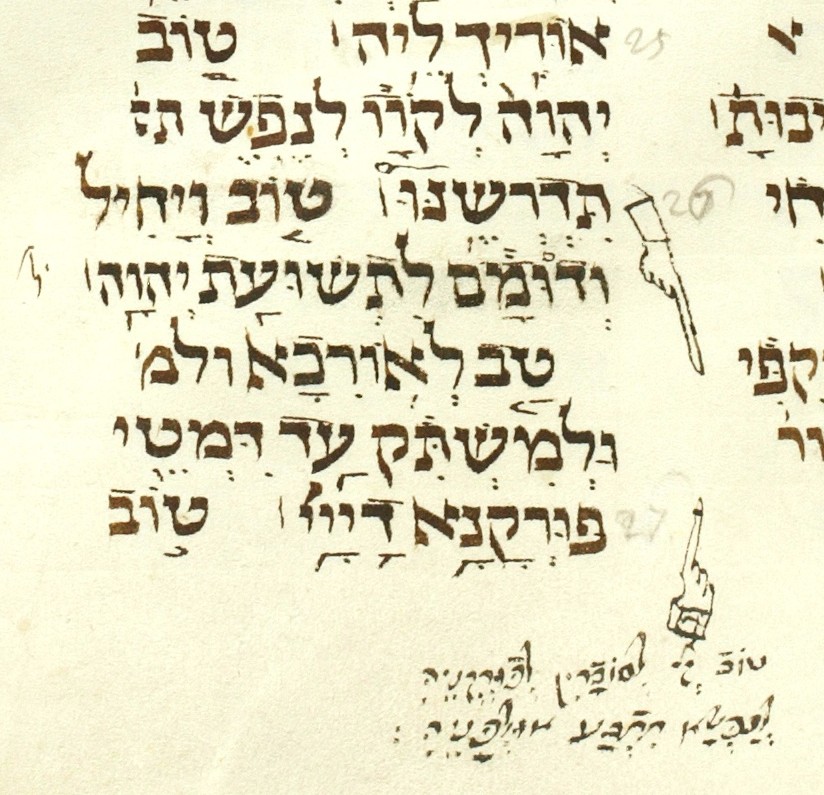

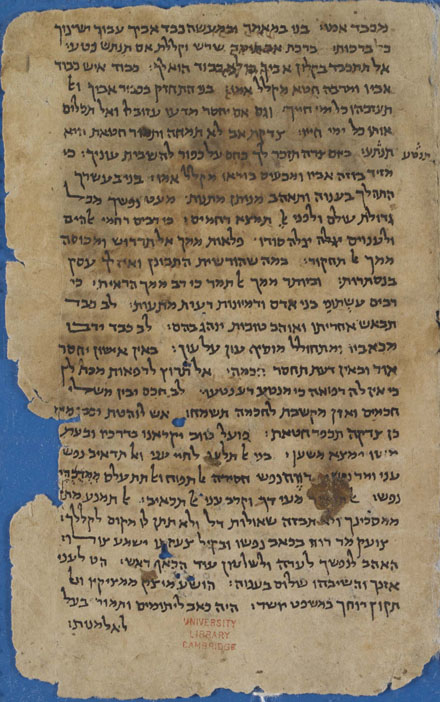

From The Rabbinic Targum of Lamentations: Vindicating God:

INTRODUCTION

לָמָּה לָנֶצַח תִּשְׁכָּחֵנוּ תַּעַזְבֵנוּ לְאֹרֶךְ יָמִים׃

“WHY HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN US COMPLETELY?” (Lam. 5.20)

Tragedy transcends time and space. What is surprising is that we are surprised when tragedy befalls us. In the last century the world witnessed countless atrocities including two world wars, multiple incidences of genocide, and terror including, but not limited to, the attacks upon the World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. But these are just the “headlines” of the recent past and those events that affect western culture; it does not even include the hundreds killed in Israel over the last three years. Across the globe and throughout history there have been similar acts on varying levels of destruction. By now you would think that we would be used to the ability of humans to harm each other. As Jeremiah told Hananiah, “The prophets who preceded you and me from ancient times prophesied war, famine, and pestilence against many countries and great kingdoms.” War has and will always be with us. It is a sign of the true value of humanity that we continue to be appalled and to ask how such brutality could possibly happen.

As I write this introduction many months have passed since the events of September 11, 2001 and yet I, and many across the world, still struggle to comprehend what happened. We struggle to understand the evil acts carried out by humans on fellow humans. For those who believe in a God who cares for this world, such events bring even this fundamental belief into question. In fact, for Alan Mintz, the definition of “catastrophe” in Jewish history is not so much a function of the physical suffering as it is the challenge to the relationship between God and Israel. “The catastrophic element in events is defined as the power to shatter the existing paradigms of meaning, especially as regards the bonds between God and the people of Israel.” [mfn]Hurban: Responses to Catastrophe in Hebrew Literature

[/mfn]

For every story or anecdote that came across the internet and was viewed on the nightly news recounting someone’s final heroics on September 11 there are as many and more who are asking, “Why couldn’t my husband live to see our first child? Where is God in this?” Thus as the atrocities of the Holocaust begin to recede into history the protective shelter that we children of the West have enjoyed for the last half century has been torn down. Catastrophe has once again forced its way into our lives. This is an admittedly self-centered perspective, but that is the nature of suffering. We may mourn as a nation, as a people, or even a world, but it truly becomes a lament when we sing it with our own voice, when we cry out and our “eyes are spent with weeping.” So perhaps, as a small consequence of this new shared experience, we can once again return to the Book of Lamentations and understand in some way the effect the destruction of Jerusalem and its Temple had upon the lives and thoughts of those for whom it was the residence of the Shekinah, the very presence of God.

… [138 pages later]

Conclusion

So what, if any, relevance does this study have for today? Several scholars have written recently about how and why readings of Lamentations such as found in the targum are untenable in a post-Holocaust world. TgLam is accepted since it is a product of a time long past and it would be comfortable to leave it as a theological relic. Yet I have no doubt that the destructions of 586 BCE and 70 CE were every bit as devastating to those communities as the atrocities of the Second World War are to us today. We may not, as individuals, be persuaded by TgLam’s interpretation of events, but it would be wrong of us to negate them, even when applied to modern crises. For those who accept God as a guiding and determining force in history there is, in fact, little other interpretation available. If nothing else, TgLam affirms and reminds us that there are consequences of our actions. There will be suffering in this world. The targumist asks his congregation if they will suffer for their disobedience or for the sake of the name of the Lord.

Restore us to yourself, O Lord, that we may be restored;

Renew our days as of old.

—Lam. 5.21

3 thoughts on “How do we make sense of it all?”

Chris – thanks again for sharing such insight and inspiration.

From a song, My Soul in Stillness Waits, sung at Mass this morning:

O Key of Knowledge

Guide us in our pilgrimage

We ever seek

Yet unfulfilled remain

Open to us

The pathway of your peace.