See also my essay on Targum for the Dictionary for the Theological Interpretation of the Bible.

In commenting on another, unrelated post John asked,

Would you please provide a concise definition of “targum.” I am planning to write a paraphrase with brief commentary on the Sermon on the Mount for Sunday’s sermon and make reference to the Targumim to introduce it.

I hope John will chime in with some additional context for how he thinks Targum would fit into his commentary. I often find that Christians are unintentionally appropriating rabbinic methods in an inappropriate manner. I am not suggesting that John is doing that! But I will never forget the preacher who asked me to explain midrash to her since she had recently been doing a lot of reading on the subject and wanted my opinion. When I asked why she said, “Because midrash allows you to make the text say whatever you want!” Not so much. At any rate, it occurs to me that I have not provided any such introduction here. [mfn]You can find my brief article on Targum in The Dictionary for Theological Interpretation of Scripture. Eds., Kevin J. Vanhoozer, Craig G. Bartholomew, Daniel J. Treier, and N. T. Wright, (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic Press, 2005), “Targum,” pp. 780-81.[/mfn]

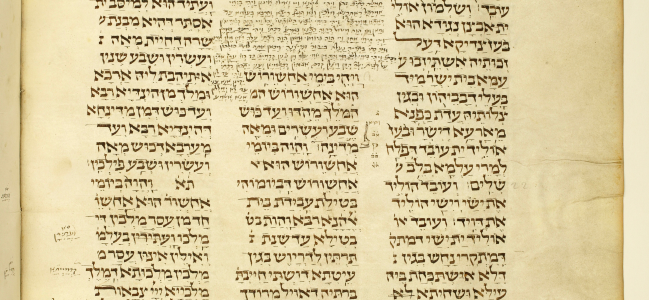

Alex Samely has a nice concise definition: “Targum is an Aramaic narrative paraphrase of the biblical text in exegetical dependence on its wording.” [mfn]A. Samely, The Interpretation of Speech in the Pentateuchal Targums (TSAJ, 27; Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1992), p. 180.[/mfn]

In slightly more accessible language, I would say it is a unique kind of translation that often incorporates interpretive material even while presenting a word-for-word representation of the original Hebrew base text.

For example, from Tg Ruth 1:4-5, the biblical text reads (NRSV)

3 But Elimelech, the husband of Naomi, died, and she was left with her two sons. 4 These took Moabite wives; the name of the one was Orpah and the name of the other Ruth. When they had lived there about ten years,

The Targum adds explanatory material while still representing equivalents for the Hebrew text, in its appropriate order. (The portions in italics are additions over the MT.) The translation is mine.

3 Elimelech, the husband of Naomi, died and she was left a widow and her two sons orphans.

4 They transgressed the decree of the Memra of the Lord and they took for themselves foreign wives from the house of Moab. The name of one was Orpah and the name of the second was Ruth, the daughter of Eglon, the king of Moab. And they dwelt there for a time of about ten years.

I think you can see how the Targumist is answering the “questions” that he felt were presented by the text, or supplying information that was necessary to “flesh out” the narrative. Naomi’s status as a widow is made explicit as too her sons status as “orphans.” (Interesting, of course, since we would say that they were not if mum is still alive, but I will save that for my commentary.)

Sometimes the additions can be far more expansive and aggadic. In a small way we find that in this example with the identification of Ruth as “the daughter of Eglon, the King of Moab.” The first verse of TgRuth, however, contains a massive expansion discussion the various famines that Israel has faced throughout its Heilsgeschichte. You can read far more of that than you probably would like in my article on the “The Use of Eschatological Lists within the Targumim of the Megilloth.”

I hope that is helpful as a quick starter definition. Let me know if you would like any clarification or further examples.

8 thoughts on “A basic definition of “Targum””

Thanks Chris

I commented because I did not wish to come across like the woman you mentioned.

I had read that a targum was a translation from Hebrew into Aramaic. I thought I had also read somewhere that it was a paraphrase, perhaps with added comments. I was seeking clarification – straight up translation or expanded paraphrase?

I wanted to paraphrase the English Sermon on the Mount and insert some brief commentary into the paraphrased text. I would tell the audience what I was going to do and then simply read my expanded paraphrase for the sermon. I haven’t written it yet, but I am guessing it will be about twice as long as the English text (I may have to do it in two parts).

What I wanted to do reminded me of what I thought a targum was, except I would be working in only one language, which I would point out. I was going to introduce my paraphrase that way, but I can just introduce it some other way.

Going to Oxford must have been great. I would loved to have done that when I was younger. The closest I got was sitting for a class at Vanderbilt (took 9 graduate level hours there) under a guy that studied at Oxford for, I think, one year. He was in All Saints or All Souls, or something like that. He should have been there in the early eighties. Legend is that the town fathers named Oxford, Mississippi “Oxford” in hopes of landing the University of Mississippi there back in the day. It worked – if the story is actually true. Did you know that?

Thanks for your help and time.

John

Thanks for the comments and clarification John. What you have in mind sounds very close to what Targum is. I avoid the term “paraphrase” because the Targum *always* ((Exceptions are so rare that they do, in fact, prove the rule.)) presents an Aramaic equivalent of the Hebrew and in order. And it does so even when that word-for-word rendering is “diluted” in massive amounts of additional material (see TgLam 1:1, for example.

So in many ways, yes, you would be offering a kind of “Targum.” In fact, the more expansive Targumim often include additions that are otherwise found in homiletic Midrashim. What sets Targum apart from Midrashim is that it is incorporating its commentary into the translation such that if you did not know the original you might well not realize it is expansive.

Oxford was a great experience in many ways. Being a poor grad students is never the best way to experience a city, but it also is a way unlike any other. We loved our time there and I learned a tremendous amount. I am pleased that two of my students will be spending their junior year there this coming year.

When I was at Tulane in New Orleans I had to regularly clarify that it was “the other Oxford” that I attended. But I did not know the legend. I will hold on to that one!

I’m with you on PJ and NFT, but how would Onkelos differ than any English translation? What I mean is, wouldn’t Onkelos be best characterized as an Aramaic translation of the Hebrew. Granted there are a few adjustments, but no where near the length of expansion as in Targum Ruth above or PJ.

One question I would find helpful if you could answer:

Do you not view Tg Ruth and others in the Mg as on the verge of Midrash, or as a sort of inbetween convention? I forget the name of the fellow who suggested this, but he’s the fellow who translated Tg Ruth and others.

You are probably thinking of Alexander Sperber who famously said that the targumim to the Megilloth “are not Targum-texts but Midrash-texts in the disguise of Targum” (A. Sperber, The Bible in Aramaic Vol. IV A, The Hagiographa, (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1968), p. viii). Certainly the Targumim of the Megilloth are paraphrastic in the extreme, but even in their exegetical excess they *always* present an Aramaic equivalent to the Hebrew vorlage in order. This is important when defining a genre and is something that Midrash does NOT do. A Midrash (and we can speak of various things as “Midrash,” a discreet interpretation of a single passage, a pericope, if you will, the genre of Midrash, or a Midrashic collection) is not concerned with representing the entirety of the biblical text. Large swaths of biblical text are not commented upon at all and yet a Targum of that text will still faithfully produce an Aramaic rendering of the text, no matter how little exegetical attention is paid to it.

If you consider TgLam 1:1-4 (and here see my early article “Targum Lamentations 1:1-4: A Theological Prologue“) you find massive amounts of material added. Yet the MT is represented in order. Once you move beyond those first few verses the rest of the book is translated largely verbatim, with only so many additions as needed for “prosaic expansion” (the Targumic practice of *always* rendering poetry into prose).

Back to your first point that TgOnk is fairy literal, like any English translation. This is an open debate (is Aramaic Job at Qumran a Targum?) we could be satisfied with just saying it is an Aramaic translation. I think there is probably enough deviation and as it is within the larger context of Jewish interpretation I think it fits as a Targum. (And a reminder that in its strictest sense the term תרגם simply means “translation.”)

Yes, it was Sperber. Thanks. I’m in total agreement with you here, and a bit disappointed that you have already articulated my point of disagreement with Sperber–I was hoping for an article out of it. In discussing this issue in our Tar Ar seminar, I suggested that no mater how expansive the Targumist is with providing background, he continuously comes back to the text, contra midrash.

Has anyone officially taken up Sperber on this issue?

I know that many scholars including me have rejected his assertion in the body of other works. I am not sure if there is any specific article that takes that on as its focus. Philip Alexander has an article or two defining Targum that might have this discussion.

Rob, I meant to tell you that we are actually dealing this issue in tomorrow morning’s session of the IOTS. Alex Samely, Philip Alexander, and Robert Hayward will be tackling the question. Should be good. I will try and record it, if they let me.