What is “fair”?

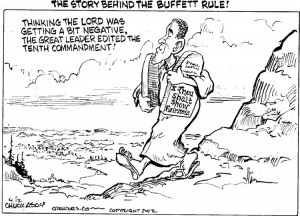

This post is not about “the Buffet rule,” but it is. That is to say, the proposal itself is obviously fairly complex and I think does deserve consideration (but Annenberg has found that this argument is fundamentally flawed in that “— on average — high-income taxpayers pay higher rates than those in the middle, or at the bottom for that matter”). What this post is about is rhetoric and morality.

The Democrats such as Barbara Mikulski argue that this is about paying “your fair share.”

“I support the Buffett Rule because I do believe in fundamental fairness. That if you live in the United States of America, that you benefit from the United States of America, both its national security and its public institutions, that you need to pay your fair share.

“This is what America is all about: fairness and that we’re all in it together.”

I do believe that in America we hold to a fundamental myth about fairness and I think that ought to be our goal. The challenge is in defining what is “fair” and my “share.” There is no doubt that everyone in America (regardless of citizenship or taxation level) benefits from our national security, road systems, and so on. Someone like Warren Buffet is not very likely to be putting much strain on the system nor benefitting from the various government programs. He could take his social security and theoretically could not carry health insurance and simply use the safety nets available to him. If he is like the wealthy people I have known [mfn]That is one aspect of being a dean that is so very curious. I know and am in regular contact with a number of people who earn a million dollars or more, often much more, a year.[/mfn] when it comes to health care for them and their family, they do not rely upon government programs. The wealthy get the best healthcare they can find. I cannot afford to do that nor can the vast majority of Americans.

Now we can argue whether that ought to be the case on moral grounds, but my point here is that we cannot say that the überwealthy are not paying “their share.” They tend to take far less from the system and yet their 20% is FAR greater than my 30%. Should a person’s “share” be determined by how much they actually use?

In almost all other contexts that is what we would expect. Let’s say that we go out to dinner at the SBL conference. There are 10 of us and everyone keeps their meal to about $25. I, on the other hand, order the prime rib with garlic mashed potatoes and green beans, followed by a Boston cream pie. My portion comes to $56. I argue that we should simply split the total bill 10 ways, after all there were 10 of us. Would you think that was fair? I doubt it. Or, to follow the Mikulski logic, since one of the other 10 people is actually a CEO and makes more than all the other of us at the table, his “fair share” would be to pay for much more than his $25, say $200 of the total bill since, after all, he earns so much more than the rest of us. Is that “fair”? It is certainly not a “share” in the usual sense of the term.

A moral, even biblical, argument

My complaint is with the rhetoric of “fair share.” That isn’t really what Mikulski, Buffett, and Obama are arguing even though that is what they are saying. Yes, Warren’s secretary is paying at a rate of 30% and Mitt is paying only 16%, but his 16% is a LOT more in actual dollars. Of course that 16% or even 30% is likely be far less of an impact on Warren’s secretary than even 15% would be to her. (Although my guess is that Warren Buffett’s They are appealing to our sense of “fairness” but they are really making a moral argument. This is actually a biblical argument.

From everyone who has been given much, much will be demanded; and from the one who has been entrusted with much, much more will be asked.that says, in effect, to whom much has been given much is expected. — Luke 12:48

The context of that passage is actually quite challenging to those who have been entrusted with “much.” The slave (and in the context the slave is the religious leaders while the master is God) who has been put in charge of the household, i.e., given much responsibility and corresponding benefits such as money and position, is expected to take his position seriously and fulfill his master’s wishes by taking care of the household and treating the other slaves well. If he does not…

45 But if that slave says to himself, ‘My master is delayed in coming,’ and if he begins to beat the other slaves, men and women, and to eat and drink and get drunk, 46 the master of that slave will come on a day when he does not expect him and at an hour that he does not know, and will cut him in pieces, and put him with the unfaithful. 47 That slave who knew what his master wanted, but did not prepare himself or do what was wanted, will receive a severe beating.

This is the fundamental assumption then, that those who earn more ought to pay more. [mfn]Of course, don’t forget that Annenberg report I linked to earlier.[/mfn] It isn’t really about it being a “fair share” since the wealthy often use a far smaller “share” of the government services than the middle-income or truly impoverished. This is, in fact, a moral position that says “since you have been fortunate enough to earn/receive a LOT of money you ought to help those who have NOT been able to earn/receive a lot of money.” I think that most Americans would agree with this sentiment. The Republican-Democratic divide arises over how that help ought to be implemented: through the government or private charity.

The sticking points are what taxes should support and the implementation of taxation. [mfn]Did you know that Abraham Lincoln was the one who first instituted an income tax? The Supreme Court later ruled it unconstitutional but Congress then enacted the system we now know. Also, Lincoln died on April 15, 1865. April 15 is, of course, Tax Day…. [/mfn] If we really want to try and get at a “fair share” approach then a flat tax seems reasonable. In such proposals everyone should simply pay a set percentage, say oh, let’s pick 9%, of their income. Mitt Romney’s 9% is going to be a LOT more than my 9%. That would then be “fair” since it is proportional to earnings, even if it is still not proportional to usage. Of course for someone earning $20k that 9% would be a BIG hit and so we have a progressive tax structure. Again, it is an attempt to get at a “fair” system.

Of course none of that gets at the moral question. Should Mitt give more since he makes so much more? His church expects a full 10% and the Christian church(es) expects the same of their congregants.

No one said it would be easy, but it politics you can always count on it being made far more complex through the use of rhetoric.

4 thoughts on “What is a “Fair Share”?”

As a pinko commie liberal, I absolutely agree. “Fair share” is a nice talking point, but without any substance. This clip from “West Wing” sums it up nicely. Like the man said, bad writing.

But your simile with a dinner is not much better. The main problem lies in your definition of usage, which is evident from the tired old line that “the wealthy often use a far smaller “share” of the government services”. No, they don’t. They may not use Medicaid or Medicare, but that’s the only substantial difference. Otherwise they do profit from everything taxes are paying for, whether directly or indirectly, starting with the military all the way to the corps of engineers (cf. In fact, considering the amount of privatization of government services in the US, the wealthy are often the recipients of government spending.

What’s more, the difference between 40k a year and 1 million a year is not a quantitave one, but a qualitative one and here is where fairness comes in: the wealth gives the wealthy not only a comfortable and relatively care-free life, but it also gives them a certain degree of power over the not-so-wealthy ones.

I know conservatives like to turn this on its head and get all outraged about the non-tax-paying rabble voting to increase the taxes on all those poor millionaires, but that’s just perverse: either people who can afford it (and then some) will pay more OR people who cannot afford it will have to do with even less. Not to mention that the wealthy can afford good tax accountants and lawyers and thus get out of paying any taxes at all.

Plus, US taxpayers, including the ones earning less then the average 40k or thereabouts, helped save the wealthy ones and their investments in the economic fustercluck (and you can keep your nonsense about how Fannie and Freddie lending to poor people caused the mortage crisis, they didn’t). It’s only fair the wealthy repay it.

I live in a country with flat tax and I’m not sure if it’s a good idea. What the introduction of flat tax did, however, is close loopholes and reduce various deductions and exceptions. Maybe that’s the right place to start.

bulbul – You are right, analogies are never perfect. But you say”

Medicaid, medicare and all the other “safety net” programs that the US government has including unemployment, food stamps, and so on make up a fairly substantial difference. The point being that the other sorts of things (which I included like national security, roads, etc.) become the baseline. Everyone certainly benefits from those, even people who are not US citizens are tax payers but are simply present within these boarders. My (hypothetical and not necessarily my personal position) argument is that those who do take advantage of the other services are by definition using “more” of the government offerings than those who do not.

You are absolutely right that wealth shifts the balance in all sorts of ways. This is where the “too whom much is given much is expected” weight of the moral argument comes in. Of course, one could argue that those who are paying more substantial sums ought to have a greater say in governance than those who do not, but then it would not be a democracy. (That is a whole different can of worms, e.g., Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission.)

Of course we have not talked about all about those people who do not pay any income tax. The figures are that anywhere from 40% in good economic years to 51% in bad do not pay any income tax.

This could be squeezing the parable a little hard, but, in the Parable of the Talents, the five talent man did not earn more than the two as a return on investment, but only in quantity. Thus what he “paid” to the master was more in a sense, but also the same in another sense. They were rewarded equally, so I guess the Master was equally pleased.

Perhaps it is “fair” for the wealthy to pay a higher rate, or, perhaps not. But, either way, I’m not sure a Biblical argument can be made for a progressive tax structure. The OT tithe was not progressive.

As my brother is fond of saying “this is an issue that has a lot nuance.” Of course, I am no longer sure it should.

Fact: The complicated tax system doesn’t work. (and yes, I believe at least in this case complicated and nuance are synonyms.) I realize there are many ways to view “doesn’t work” but the most clear example is that our elected officials are rewarded for spending, and for not taxing.

Having 51% of the population not paying taxes, and having the elected officials answerable to the majority of the voters, tends toward a forcing function of runaway spending while answering to those who provide campaign financing–the wealthy.

Implementing a flat plan (and FTR, I supported Kane’s 999 plan) would give everyone “skin in the game” and, if made to eliminate/ban the creation of “nuanced rules” should eliminate the influencing of politicians to give those breaks.

Just a thought–sometimes simpler IS better.

As John wrote–Tithing is a flat rate.