I should preface by saying that although Prof. Vermes had formally retired by the time I was doing graduate work at Oxford I had the great honor to attend seminars and sessions with him and to copy edit DJD vol. 26 which he wrote with Philip Alexander. I can only hope to someday produce half the work at half the quality that he has. That being said, a few comments about the interview, mostly on GV comments about the resurrection.

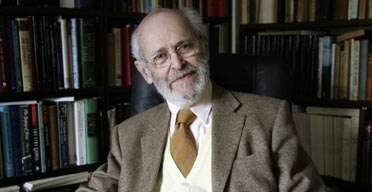

Geza Vermes: Questions arising “John Crace meets the professor of Jewish studies whom many dub the greatest Jesus scholar of his generation.”

The Resurrection is the final instalment of Vermes’s Jesus trilogy, which began with The Passion and The Nativity. Vermes again adopts his trademark forensic textual analysis to separate fact from myth: “I wanted to explain exactly what the New Testament does tell us about the resurrection. People usually rely on others to interpret the gospels for them and St Paul’s assertion of the physical resurrection has become a cornerstone of Christianity for many people. If Jesus didn’t rise from the dead, then faith is rubbish.”Yet if you look at what Jesus actually said, then you get a different picture. If he did talk about the resurrection, he forgot to write it down; so it’s more likely he didn’t. And if he did, then why did his resurrection come as such a surprise to the apostles? No one said, ‘Of course, Jesus said it would be like this’ when his tomb was found to be empty; even Mary Magdalene assumed that someone must have moved the body. Nobody’s reactions correspond to the expectation of a resurrection.”

“If he did talk about the resurrection, he forgot to write it down”? Devastating argument. Not really. I have not yet read this book, obviously, but I think this simple comment reflects a deeper problem with Vermes’ reconstructions of Jesus’ life. He is outstanding textual scholar but seems to have a very limited view of the Sitz im Leben and little imagination of how Jesus might really have lived and engaged with his disciples and the people around him. I think Bruce Chilton’s Rabbi Jesus is a nonsense work except he does a remarkably good job of painting the picture of what life would have been like in that context.

Vermes seems to imagine Jesus as a scholar like himself, taking notes and writing up his thoughts and teachings while imparting them all clearly to his students. This certainly does not align with any evidence we have of other Jewish teachers of the time and later. On the other hand, we do know that many teachers of the day believed that there would be a resurrection, indeed it was a hot debate of the day.

There are two key issues to be teased out here, I believe. One is the concept of the resurrection as general belief. As GV notes, the idea of the afterlife predates Christianity, but more specifically the notion of the resurrection and judgment humanity is found within the Judaism within which Jesus dwelt. In 2 Macc. 7:9 the tortured young man says “You accursed wretch, you dismiss us from this present life, but the King of the universe will raise us up to an everlasting renewal of life, because we have died for his laws.” And of course Daniel 12 famously states:

2 Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt. 3 Those who are wise shall shine like the brightness of the sky, and those who lead many to righteousness, like the stars forever and ever.

This is simply to state what is obvious to most who read this blog, and is of course obvious to GV I am sure, which is that there were many Jews of the first century who believed that a day was coming when God would raise humanity from the dead and judge them according to their deeds.

The second issue that is often not so clearly stated, is the notion that Jesus, or anyone else for that matter, should rise from the dead before the day of judgment seems to be without antecedent. Thus it would seem entirely plausible that Jesus could speak of the resurrection without the disciplines realizing that he was speaking of something specific to himself and other than the general resurrection at the day of judgment. (Consider John’s account of Martha’s response to Jesus when he tells her that Lazarus shall rise again, John 11:24.) The surprise of the women at seeing the tomb empty would be understandable, even if they did believe that they would all be raised again at the last.

Finally, there is the tertiary question of a bodily resurrection. In the interview GV says,

“Jesus had promised to be with them and he was,” he argues. “It’s a resurrection of the spirit in the hearts of believers. The idea of an afterlife predates the Christian era and the preaching of eternal life is well attested; a physical resurrection is not essential to a belief in spiritual survival.”

The problem with this suggestion is that it is far less probable than a simple statement that the resurrection of Jesus never happened or the perception of the resurrection as recounted in the Gospels. Why? Because the scenario suggested by GV above (and others before him) does not fit in with anything we know of Jewish expectations. It is not so much that they expected a bodily resurrection, after all, the expected it to be at the end of times, I would suggest that for most involved within the first century debate the state of the corpus was not an issue one way or the other. Rather the conception of some “spirit in the hearts of believers” has even less antecedent than that of individual, bodily resuscitation. Sure, we could throw in NT passages regarding the indwelling of the spirit and things like that, but this is not what GV is describing. He apparently envisions some sort of spiritual reminiscences of Jesus in their own actions. “Vermes goes on to argue that subsequent sightings of Jesus are best understood as visions in which the apostles felt his charisma working as it had done when he was alive.” Regardless of what one thinks of the texts’ historical accuracy, this sort of reconstruction has no basis in any evidence available. So why should we find it preferable?

Always feeling the need for caveats I will add that I say the above not as an argument for the text or traditional understanding of the resurrection of Jesus, but rather as a question of who we “do” history. If we as historians offer another reading of an historical event (real or recounted) then we ought to have some evidence in support of our alternate view and at the least our new reconstruction ought to be more plausible within the original historical context. A “spiritual resurrection” theory sounds more like trying to appease someones’ consciouses rather than a legitimate historical assessment.

It is Holy Week so this is just one of many such books, films, and other attempts to capitalize on the season. Finally, Jim Davila points out that “Also, A. N. Wilson has a very negative review of The Resurrection in the Telegraph.” That isn’t half of it. Very, very negative. [And Crossley has a review of Wilson’s review here.]

I shall have to get the book and see for myself soon. In the meantime, feel free to use the convenient link below to order the book. (If others can capitalize on the season I can at least try and get 4%.)

8 thoughts on “The Guardian profiles Geza Vermes and we discuss the resurrection.”

“[T]he notion that Jesus, or anyone else for that matter, should rise from the dead before the day of judgment seems to be without antecedent.”

There are at least two references in the Jewish scriptures to individuals being resurrected: the Dry Bones in the presence of Ezekiel, and the son of the Shunamite woman through the intercession of Elisha.

Thanks Joe. The reference in Ezekiel (Ez. 37) is a vision of what how God will raise up again the nation of Israel and the context does not suggest that it is referring to the resurrection. In the cases of the Shunamite woman and Lazarus or the young girl of Mark 5, these are all instances of what many call “resuscitation” to distinguish from resurrection. That is to say, they were brought back from death (or near death) BUT then went on to live their lives until such time as they died. Jesus, on the other hand rose from the dead in a transformed body (he passed through walls, etc.) and ascended to heaven. These are key distinctions.