UPDATED – Excursus below.

That is overstating the case and an example of really bibliogeeky link baiting. (Can we have a competition to see who has the geekiest or the worst?) But it does convey the sense of what I think is going on. As I posted earlier, I have submitted this as a proposal to the International SBL for this summer and have already completed a draft of the paper. I do not want to share the whole paper here now, but I am happy to put forward the basic premise. I am curious what sort of responses it all receive.

Proposal

The author of 1 Maccabees is unknown, as is the precise date of composition. While our only sources of the tradition known as Hanukkah come to us through 1 and 2 Maccabees, neither book was preserved in the Jewish canon. The purpose of 1 Maccabees is primarily theo-political. “The author wants to show how God used Judas and his brothers to remove the yoke of Seleucid oppression, and to explain how the Jewish high priesthood came to reside in this family.” [mfn]Daniel J. Harrington, Invitation to the Apocrypha (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999), 122.[/mfn] It is perhaps this emphasis on the divine guidance of a Jewish uprising against foreign oppressors that led to the suppression of 1 and 2 Maccabees in the wake of failed attempts to overthrow the Romans. Even so, the influence of these texts clearly continued into the first few centuries of the Common Era.

The author of 1 Maccabees is unknown, as is the precise date of composition. While our only sources of the tradition known as Hanukkah come to us through 1 and 2 Maccabees, neither book was preserved in the Jewish canon. The purpose of 1 Maccabees is primarily theo-political. “The author wants to show how God used Judas and his brothers to remove the yoke of Seleucid oppression, and to explain how the Jewish high priesthood came to reside in this family.” [mfn]Daniel J. Harrington, Invitation to the Apocrypha (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999), 122.[/mfn] It is perhaps this emphasis on the divine guidance of a Jewish uprising against foreign oppressors that led to the suppression of 1 and 2 Maccabees in the wake of failed attempts to overthrow the Romans. Even so, the influence of these texts clearly continued into the first few centuries of the Common Era.

The influence of 1 Maccabees can be seen in chapter 11 of the so-called “Epistle to the Hebrews” found in the New Testament. Also of unknown authorship and date, Hebrews is a curious document that, although circulated among Paul’s writings and described as a letter, defies the usual epistolary conventions. Indeed, it strikes most modern commentators as having more in common with sermons than letters. Buchanan describes it as a “homiletical midrash” and his evocation of Jewish exegetical traditions is appropriate. Although Hebrews is a Christian apologetic text, it is also fundamentally a Jewish text written for other Jews. Chapter 11 is famous for the author’s exhortation to his audience that it is “by faith our ancestors received approval” (Heb 11:2). He then proceeds to list individuals from biblical and Jewish history “who through faith conquered kingdoms, administered justice, obtained promises, shut the mouths of lions, quenched raging fire, escaped the edge of the sword, won strength out of weakness, became mighty in war, put foreign armies to flight” Heb 11:33-34.

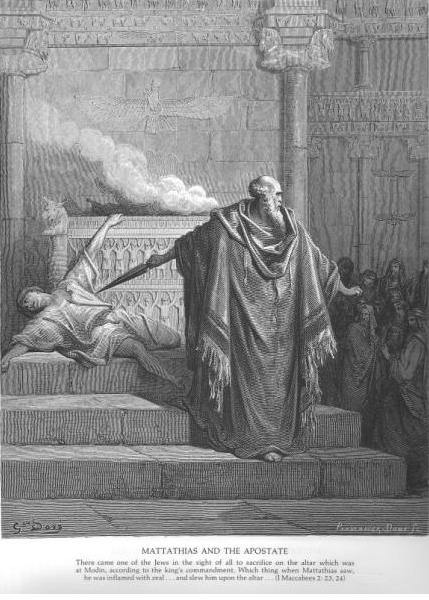

In commenting upon this list, scholars often refer to 1 Macc 2 and Mattathias’ dying exhortation to his sons that they “remember the deeds of the ancestors” 1 Macc 2:51. Mattathias goes on to list great heroes from the Bible, from Abraham to Daniel, who all did mighty works and were zealous for the law and so gained honor. While the superficial similarities are obvious and contrasts between the two lists are sometimes made, what has gone unnoticed is the fact that Heb 11 should be read with and against 1 Macc 2. The author of Hebrews not only knew of this passage but also assumed his audience would know it as well.

….

Excursus

Comments made below and on twitter make me realize I should articulate why I have not included Sir. 44-50 and Wisdom 10 in this comparison. There are certainly similarities between these four texts that are worth examining. [mfn]Eisenbaum, Pamela Michelle. The Jewish Heroes of Christian History: Hebrews 11 in Literary Context. Society of Biblical Literature Dissertation Series 156. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1997.[/mfn] but where 1 Macc 2 and Heb 11 share key traits to be analyzed below, Sir and Wis are distinct from both. In the case of Sir we find a true encomium, praising the individuals without explicitly offering them as examples to be emulated. Wis 10 is yet another sort of text. In it “wisdom” is personified and presented as the savior, the agent by which God brought about his preserving work in his people Israel. Wisdom is the active agent rather than being something, like faith or great deeds, that the reader is to have or exhibit. The genre, style, and theology is something altogether different than what is found in either 1 Macc 2 or Heb 11.

….

Summary of the Argument

Most commentators [mfn]Particularly see:

Cosby, Michael R. The Rhetorical Composition and Function of Hebrews 11 In Light of Example Lists in Antiquity. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1988.

Eisenbaum, Pamela Michelle. The Jewish Heroes of Christian History: Hebrews 11 in Literary Context. Society of Biblical Literature Dissertation Series 156. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1997.[/mfn] do note that 1 Macc 2, like Hebrews 11, has a list of biblical heroes and presents them in chronological order. They then dismiss 1 Maccabees as not being similar enough to have been a literary influence on Hebrews. That may be so, but I contend that theologicaly there is a rather direct influence. The passages function in much the same way (so in that sense we might say there is a literary influence) as it encourages the audience to remain faithful in times of persecution, but the vital difference is their choice of emphasis. The author of 1 Maccabees emphasizes the “deeds of our ancestors” whereas Hebrews, of course, extols faith as the key to survival and salvation.

There is, of course, a long and deep history of debate surrounding faith and the law in the New Testament and I will not enter into that debate now. Yet the contrasting approaches of Heb 11 and 1 Macc 2:49ff. must be acknowledged, particularly because they share such similarities. An audience who knew 1 Maccabees would hear the words of Hebrews as building upon that earlier argument and getting behind it. The author of Hebrews is arguing that what motivates one to do deeds in keeping the law is vitally important and, in turn, should alter one’s expectations of reward.

So that is it, in a nutshell. The author of Hebrews is, in a very real sense, offering a derash upon 1 Macc. 12. It is offering a reading of that earlier author’s contention that God’s people should considered the positive examples of those who went before and to emulate them. The difference is that the author of Hebrews asserts that just their deeds are not enough and, unlike Mattathias, his concern for his audience is not that they should have “honor and a great name,” but that they should be faithful in this life and so be saved before the throne of God. Obviously the meaning of Hebrews 11 stands on its own. Yet when considered against the backdrop of Mattathias’ speech it stands in sharp relief.

9 thoughts on “Hebrews 11 is a Midrash of 1 Macc. 2”

Ah – I now see why you wanted a plausible ground for knowledge of 1 Macc in the first century AD!

The reuse of “scripture” interests me greatly. I wonder, though, how you might address a couple of issues that immediately come to mind. Given the existence of other summaries of the deeds/works of ancestors – as in Sirach, Wisdom 10, etc – what factors show that Heb 11 is engaging specifically with 1 Macc 12 and not with this “genre”? Also, are we able to trace, from Heb 11, any specific recourse to Paul’s argument in passages such as Rom 4, which the author might be treating as one “mediator” between this genre of great deeds of Jewish ancestors and the early Christian exposition of faith?

Deane – Yes, Sirach and others are similar, but different enough that I did not include them in the study. The key bit is that Sir. is more of a true encomium, simply praising the individuals. 1 Macc. 2 is presenting the list as exemplars, explicitly encouraging the audience to emulate their behavior (“great deeds”) so that they would have great honor and so that their name would be known. Hebrews 11 uses faith in the same way thus the reason for the comparison.

I see. Thanks, Christian!

Who wrote the book of Hebrews?

Keefa, no one really knows. Some traditions attribute it to Paul, but that seems unlikely (language, style, and content vary quite a bit). I don’t see a reason to attribute any particular name to the author. We can say certain things about him (or her, but unlikely that it was a woman). For example, the author not only knew the Bible (remember at this point it would be the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament) quite well, but at times prefers the readings of the LXX, the Greek version of the Bible, such as in Heb. 11:5, “For it was attested before he was taken away that ‘he had pleased God.’” He also displays exegetical techniques that are very similar to those of Jewish commentators of the day. So we can say that he was (in all probability) a Jewish convert who was at least conversant with Greek if not living in the diaspora and was well learned in Jewish biblical interpretation.

thank you I appreciate your nice sound response

I think you’re basically right here. I agree Hebrews wants the reader to read ch. 11 with and against 1 Macc 2.

One other thing to consider: I’ve been spending a lot of time with 1 Maccabees for my dissertation, and one thing that has continually stuck out has been its propagandistic tendency to portray the Maccabean Revolt as the beginning of Israel’s restoration/end of the Age of Wrath and the Hasmonean house as the rightful rulers in this new age.

That angle—and 1 Maccabees’ strong connection to Israelite history and eschatological expectations—gives Hebrews some traction to make a case for Jesus /actually/ having brought about the restoration hoped for in 1 Macc, with the subtle changes in emphasis and which figures are mentioned/alluded to serving that point.

Jason – You make an excellent point. There is no doubt that 1 Macc has an agenda to show that the Hasmoneans’ ascent and success is due to God’s guidance and provision. It would make complete sense, in that light, that a Jewish-Christian community that help 1 Macc in high regard might well see Jesus’ own arrival as the culmination of that. Of course, there are still issues with how the Hasmoneans were viewed by the 1st century…not with uniform favor, but I think it is a point worth pursuing.