As I am working on my new book on Targum Ruth I am also editing my doctoral thesis to get it into eBook form (well, truth be told, an undergrad is doing the editing). One matter that I laid out in the thesis and my book that I think is still valuable is the need for us as scholars to be explicit in our methods. Or at least to be as conscious of them as we can be. In the following I lay out my argument for what I call “the Exegetical Method” for analyzing Targumic Literature. I was working on Targum Lamentations at the time so the examples all come from that text. For citations (there were far too many footnotes to sort out and, as I have suggested before, I hate endnotes) please see the PDF of my thesis available here.

The Exegetical Method

Although targumic literature has been studied extensively over the last several decades, there has yet to be a systematic presentation of a critical methodology for the reading and interpretation of targumic texts. There are critical studies of the targumim, but they have tended to focus upon textual and recensional issues and relied upon relatively self-evident methods of analysis. Several scholars have focused upon the literary and theological aspects of the targumim, but they tend to articulate the method with which they will approach the particular text at hand rather than argue for a more general method that would be usable in the study of other targumim. On the other hand, there is the invaluable work of Klein, who examines many different targumim in order to reveal patterns in the translational method of the targumist.

It would appear that the field of targumic studies is lacking what biblical studies has taken for granted for the last 100 years: an armory of articulated critical methodologies from which we might choose that which best applies to a given text and approach. In this section I will present a general critical methodology that can be applied to targumic texts in order to determine their exegetical, or theological, perspective. This proposed method for discerning the exegetical perspective of a targum, which I will refer to as the “Exegetical Method,” involves three main steps.

Survey of MT

The basic textual reading and theological message of MT must be determined so that it is possible to see where the targumist follows or departs from what we might hesitantly refer to as the “simple meaning” of MT. For example, the biblical text of 2.22 reads:

You invited my enemies from all around

as if for a day of festival;

and on the day of the anger of the Lord

no one escaped or survived;

those whom I bore and reared

my enemy has destroyed.

Clearly the Hebrew text is a description of the destruction of Jerusalem and the massacre of her people. The targum, however, transforms the verse so that it now reads:

May you declare freedom to your people, the House of Israel, by the King Messiah just as you did by Moses and Aaron on the day when you brought Israel up from Egypt. My children were gathered all around, from every place to which they had scattered in the day of your fierce anger, O Lord, and there was no escape for them nor any survivors of those whom I had wrapped in fine linen. And my enemies destroyed those whom I had raised in royal comfort.

In the targum the verse has been completely altered so that the verse has become a day of liberation for Israel, rather than a day of mourning. The nature of the targumic additions cannot be fully appreciated until they are compared with the base text of MT.

It is therefore important that we survey MT before we begin our study of the targum so that we will be able to perceive any changes which the targumist may have made to the text in the process of creating the targum to Lamentations. In so doing we will also summarize current biblical scholarship on the Book of Lamentations. This is necessary because modern scholarship has revealed much about Lamentations, particularly through linguistic analysis, which will provide us with a better understanding of the targumist’s source text. Our reliance upon this scholarship will, however, be limited because the concerns of the targumist were often very different than those of the modern biblical scholar. A general survey of the Book of Lamentations will follow this chapter, but each verse must be examined individually, therefore frequent references will be made to relevant scholarship throughout the Commentary (Chapter 3). Our next step in the methodology is the Exegetical Commentary which involves an examination of the individual verses of both MT and the targum.

Exegetical Commentary

The second step requires two phases:

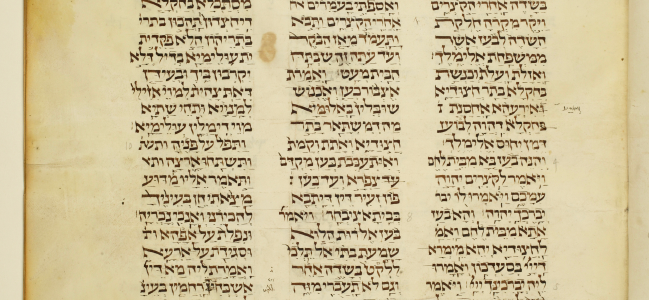

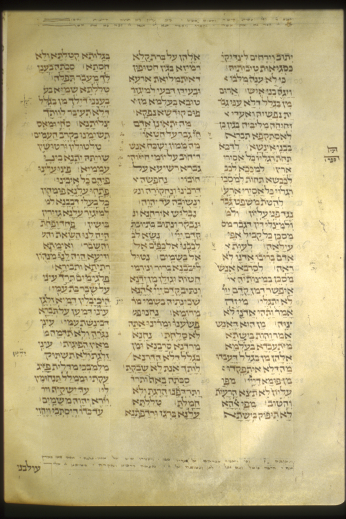

Quantitative Analysis Before we begin to analyze how the targumist has come to a particular reading of the Hebrew text we must first determine the basis of the targumic text. Thus the first step is to decide which MS or edition of the targum will be used. The targum should then be translated into English (or another modern language). This translation will serve as an aid to the reader and an indication of our interpretation of the targum. Part of this translation process is determining which Aramaic terms correspond to the Hebrew found in the biblical text. Observing where the targum goes beyond a simple one-to-one correspondence with the Hebrew will help to reveal how the targumist has interpreted the biblical text.

Such a task would appear on the surface to be a simple one. Merely compare MT with the targum and italicize the portions in the Aramaic text which are “left over.” Often, however, it is not such a straight forward matter. While the targumist will frequently provide a verbatim rendering of the Hebrew, it is also common to find an element of the Hebrew represented by more than one word or phrase. So while it is easy to see in 1.1, for example, where the targumist has added a lengthy preface to the targum which identifies Jeremiah as the author of the Book of Lamentations, even in this first verse we encounter difficulties in determining exactly what portion of the Aramaic corresponds to the Hebrew text.

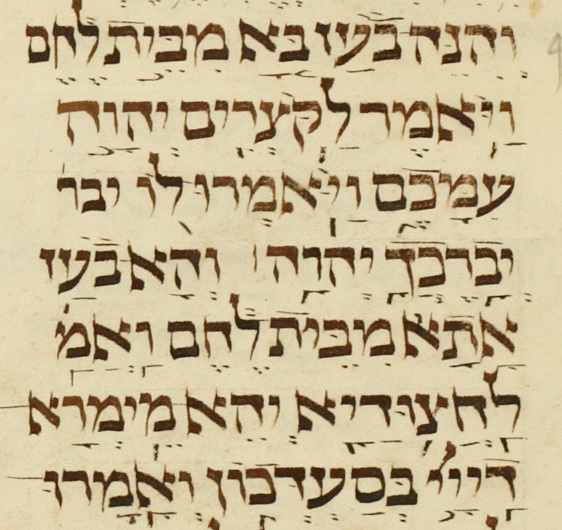

The first word of the Book of Lamentations, איכה, is represented in the targum not once, but three times. In the first instance איכה is translated in its operative sense by the Aramaic איכדין. “Jeremiah the Prophet and High Priest told how it was decreed that Jerusalem and her people should be punished with banishment.” In the other two instances the term is retained in its original form, איכה. By the rabbinic period איכה had come to mean “lamentations,” thus Jeremiah declared that Jerusalem “should be mourned with √ekah” just as God mourned over Adam and Eve “with √ekah.” So, which occurrence of איכדין/איכה should be identified as corresponding to MT’s איכה? Or, to phrase the question in more general terms, how do we determine if an Aramaic term corresponds to the Hebrew?

It is surprising to note that there are, to the best of my knowledge, no publications or comments written by modern targum scholars outlining the method of analysis used in order to determine which portions of the text are targumic expansions and therefore should be italicized. I shall therefore endeavor to set forth some general guidelines to indicate the method employed in this thesis. The principle followed in this thesis and translation is that if the Aramaic term in question occurs in the same order as the Hebrew and functions in the same manner as the Hebrew word it shall be considered as equivalent. In this work we will follow the convention found in The Aramaic Bible series which indicates all other material in the translation by the use of italics. This definition of correspondence must remain broad since not all of the criteria listed will be determinative in every instance. Returning to our example, in 1.1 all three Aramaic terms which might correspond to איכה are in the proper order; that is, they occur before the targumist has translated the subsequent words of the biblical text. Thus, the criterion of word order is inconclusive. However, it is only the first instance which functions in the same manner as the original איכה of the biblical text. The other instances are nouns, but איכדין is an interrogative and therefore is considered the equivalent of MT’s איכה.

Similarly, elsewhere in 1.1 we are confronted with two phrases which might be considered as corresponding to ישבה בדד.

ענת מדת דינא וכן אמרת על סגיאות חובהא אשתדר ומה דבגוהא בגין תהא יתבא בלחודהא כגבר דמכתש סגירו על בסריה דבלחודוהי יתיב

The Attribute of Justice spoke and said, “Because of the greatness of her rebellious sin which was within her, thus she will dwell alone as a man plagued with leprosy upon his skin who sits alone.”

The first instance, יתבא בלחודהא, most closely represents the Hebrew text since Jerusalem is the subject (as in MT) and the word order matches MT. The subject of the second phrase, דבלחודוהי יתיב, is not Jerusalem and the word order is reversed, therefore it should not be considered as corresponding directly to the Hebrew text.

Finally, in 1.7c the Hebrew text reads “her people fell into the hand of the foe” (בנפל עמה ביד-צר). Our targum renders this phrase, “her people fell into the hands of the wicked Nebuchadnezzar” (נפלו עמהא בידוי דנבוכד נצר רשיעא). The basis for this translation is the occurrence of the letters צ and ר at the end of Nebuchadnezzar’s name and it is clear that נבוכד נצר does indeed represent the Hebrew צר since it occurs in the same order and functions in the same manner as the biblical text. Since the basis of this similarity is the ending צר of נבוכד נצר these letters are not italicized and the name therefore appears in this translation as “Nebuchadnezzar.”

As stated earlier, these guidelines are broadly defined and each verse must be dealt with individually. The use of italics is intended merely as a device to aid us in the study of the targumist’s reading of MT. There will, of course, be differences of opinion as to whether or not the Hebrew is represented in a given Aramaic rendering, but where TgLam offers multiple or less obvious readings of MT my decision to identify a given Aramaic term as corresponding to the Hebrew will be explained within the commentary. It should also be remembered, that while we are attempting at this phase of the analysis to identify which Aramaic term most closely corresponds to MT, when a Hebrew term is represented by more than one Aramaic term, each occurrence is (obviously) related to the original text. The relationship and function these multiple, or divergent readings, within the targum is the goal of the next stage of analysis.

Qualitative Analysis

In this phase the content of the targum is studied in detail. This will include not only the study of targumic additions, but also the examination of the targumist’s translation technique. It is commonplace to say that “all translation is interpretation” and it is no less true for the targumim. Thus even where there appears to be a word-for-word equivalence with MT or where there is little additional material added, the targumist’s word choice, syntax, and other subtle traits of the targum must be analyzed. For example, with few exceptions, TgLam represents the Hebrew בת, “daughter,” with כנשתא, “congregation.” The targumist has represented the Hebrew word with a single Aramaic word, but it is by no means a literal translation. We shall see that the use of this term has a dramatic effect on the meaning of the text and is used as a rhetorical device to increase the impact of Lamentations on the audience. Our analysis of the targum must therefore involve the careful study of the targumist’s translation as well as the additions to the biblical text.

The examination of targumic expansions will involve determining if the addition contradicts, supports, or transforms the aforementioned “simple meaning” of the biblical verse in question. (This can occur in a variety of ways including direct contradiction of MT and sustained argument bolstered by the placement of additions.) Furthermore, an attempt must be made to determine if the exegetical tradition represented in the addition is attested in other rabbinic texts. Considering the vast corpus of rabbinic material this represents a significant challenge, but it is vital that such an investigation be a part of this analysis. The primary texts examined in this study include the major midrashim, especially LamR, the targumim, the Mishnah, and the talmudim.

If the tradition is not found in other rabbinic sources, we may attribute the additions to the broader context of rabbinic tradition or the ingenuity of the targumist. Often the targum to a given verse does not have additional material, there may be a one-to-one correspondence between the Hebrew and the Aramaic, but the way in which the targumist has translated the verse is equally important. In this case the targumist’s word choice must be considered in order to determine if he has chosen specific terms or phrases which might carry theological overtones.

Over the last twenty-five years great advances have been made in our understanding of the targumic method of translation. This is due largely, but not exclusively, to the work of Michael Klein and his analysis of the translation techniques of the targumim. Klein has isolated and described a variety of patterns by which the targumim transform the biblical text. These exegetical rules range from the direct and obvious addition of a negative particle to the more subtle translation of one passage in light of another. TgLam exhibits several of the more well known methods of exegesis as well as two less common interpretive techniques.

1) Converse translation. This method of translation entails direct contradiction of the biblical base text and Klein identifies three major ways in which the targumist accomplishes this. The targumist may add or delete a negative particle, “he may replace the original biblical verb with another verb of opposite meaning,” or he may resolve a rhetorical question with a declarative statement. TgLam 3.38 provides an excellent example of the last category. MT reads “Is it not from the mouth of the Most High that good and bad come?” (מפי עליון לא תצא הרעות והטוב:). The targum, however, renders the verse “From the mouth of God Most High there does not issue evil, rather by the hint of a whisper, because of the violence with which the land is filled. But when he desires to decree good in the world it issues from the holy mouth” (מפום אלהא עלאה לא תפוק בשתא אלהן על ברת קלא רמיזא בגין חטופין דאתמליאת ארעא ועדן דבעי למגזר טובא בעלמא מן פום קודשיה נפקא:). The rhetorical question of the biblical text has been replaced with the declaration that evil does not issue from the mouth of God. The targumist also goes on to add that, in fact, it is only good which is decreed “from the holy mouth.”

2) Associative and Complementary Translations. Most prevalent in TgPsJ, Klein identifies this technique as the result of the targumist “translating one passage while under the influence of another.” An example of this is found in TgLam 1.9c. The biblical text reads ראה יהוה את-עניי, but the targum translates it with חזי יי ותהא מסתכל ית עניי, apparently providing a double translation of the Hebrew ראה. The addition of the verb מסתכל is, in fact, due to the targumist bringing verse 9 into line with 1.11c which reads ראה יהוה והביטה. The targum renders this phrase with חזי יי ותהי מסתכל. The same Hebrew phrase and its Aramaic counterpart are also found in 2.20a. The Aramaic version of 1.9c is, therefore, the result of the targumist translating the phrase in light of 1.11 and 2.20.

3) Multiple readings. McNamara defines “multiple sense” in relation to the Palestinian targumim as a method of translation which occurs when the Hebrew words have more than one meaning. “Which of the meanings suits a given context can be a matter of opinion. The Pal. Tgs. often translate by retaining two or more senses for a Hebrew word.” We have already noted the example in 1.1 of the multiple rendering of the Hebrew איכה since the term had developed the meaning of both “how” and “lament.”

I refer here to “multiple readings” since our targumist will also provide more than one interpretation of a Hebrew term for purely exegetical reasons which are not necessarily based upon multiple meanings of the Hebrew. For example, the last stich of 1.1 reads שרתי במדינות היתה למס, “she that was a princess among the provinces has become a vassal.” The phrase היתה למס is represented in the targum by both והוון מסקין לה מסין and ולמתן לה כרגא.“She who was great among the nations and a ruler over provinces which brought her tribute has become lowly again and gives head tax to them from thereafter” (ושליטא באפרכיא והוון מסקין לה מסין הדרת למהוי מכיכא ולמתן לה כרגא בתר דנא). Although למס is an hapax legomenon the targumist’s double rendering is not an effort to “bring out the wealth of the Hebrew text.” Instead it is used as an exegetical device in order to heighten the contrast between Jerusalem’s condition before and after her destruction.

4) Prosaic Expansion. This method of translation is common to all targumim of poetic texts and is defined by the consistent rendering of poetic texts as prose. Passages which are translated in this manner are defined as non-literal translations that may contain minor additions that do not effect either the textual or theological message. Since this method is quite common in TgLam we will present only one example here. In 1.11 the Hebrew text reads, “All her people groan as they search for bread” ( כל-עמה נאנחים מבקשים לחם), while the targum renders this as “All the people of Jerusalem groan from hunger and search for bread to eat” (כל עמא דירושלם אניחן מכפנא ותבען לחמא למיכול). The meaning of the text has not been altered; the targumist has simply identified the pronominal suffix of עמה as “Jerusalem” and added the explanatory that they search for bread “to eat.” The terse language of the poetic text has been replaced with a fuller prose style.

The purpose of this method of translation may be understood in terms of the relationship between a targum and Scripture. The Mishnaic passages which prescribe how the meturgeman was to present the targum within the service are well known. The principle which guides these prescriptions is that the congregation should not be given the impression that the targum is Mikra. Therefore while the one who read Scripture had to read from the Torah scroll, the meturgeman was never allowed to read from a written text. Prosaic expansion may well have operated in a similar fashion. By rendering the laconic Hebrew into flowing Aramaic prose the targumist provided yet another indication that what was being presented was not Mikra.

5) Dramatic Heightening. Finally, TgLam presents us with a method of translation which appears to be unique among the targumim. It is not uncommon to find that the targumim (and rabbinic literature in general) alter the language of a biblical text where it appears to present views which were contrary to contemporary notions. These changes frequently occur through the use of converse translation. We find, therefore, in Gen. 4.14 when Cain declares, “today you have driven me away from the soil, and I shall be hidden from your face,” that the targumim reject the notion that someone can hide from God. TgOnk, TgNeof, and TgJon all alter the text so that they either state “it is impossible for me to hide from before you” (TgOnk and TgNeof) or ask rhetorically “is it possible for me to be hidden from before you?” (TgJon). Similarly, the targumim often distance God from the anthropomorphic statements of the Bible. Thus, the description in Gen. 11.5, “the Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which mortals had built,” in TgNeof becomes “The Glory of the Shekinah of the Lord was revealed to see the city and the tower.” While this practice of “softening” the language of the biblical text is common in targumic literature, TgLam demonstrates that it is not without exception.

The Book of Lamentations is often extremely graphic in describing the horrors of a city under siege and frequently speaks of God as the author and agent of Jerusalem’s destruction. It would be reasonable to expect TgLam to interpret these passages in such a way that they would no longer be offensive or challenging to the commonly held rabbinic views. It is therefore quite surprising to find that not only does our targumist retain references to God “as an enemy,” but he even introduces vivid and graphic imagery to passages which were otherwise relatively banal. The most startling example of this is 1.15. The biblical text describes God as proclaiming a time when both the young men and women of Judah would be destroyed.

The LORD has rejected

all my warriors in the midst of me;

he proclaimed a time against me

to crush my young men;

the Lord has trodden as in a wine press

the virgin daughter Judah.

The language of this verse is quite strong, it is the Lord himself who has “trodden” the “virgin daughter Judah,’ but the language of the targum is much more dramatic.

The Lord has crushed all my mighty ones within me; he has established a time against me to shatter the strength of my young men. The nations entered by decree of the Memra of the Lord and defiled the virgins of the House of Judah until their blood of their virginity was caused to flow like wine from a wine press when a man is treading grapes and grape-wine flows.

While the biblical text describes the Lord as rejecting the warriors of Judah, the targumist intensifies the image by describing the Lord as crushing them. God no longer treads on the virgin daughter Judah, but instead the targum tells us that it is “the nations” who act by “the decree of the Memra of the Lord.” The most startling change to this verse, however, is the nature of the calamity which befalls Judah. In the biblical verse Jerusalem is personified as “the virgin daughter Judah” and she has been laid low, “trodden,” by the Lord. In the targum,however, the metaphorical “virgin daughter Judah” becomes the “virgins of the House of Judah” who are raped by the invading nations so viciously that the “blood of their virginity” flows freely.

In this verse, the targumist does not distance God from actions against Judah, he intensifies the horrors described. God no longer rejects the warriors, he crushes them. Jerusalem is not razed, her virgins are brutally raped. What is the purpose of such changes to the text? As we shall see, the dramatic heightening of passages which describe Jerusalem’s punishment serve a rhetorical and theological purpose. By embellishing the (already graphic) references to Jerusalem’s suffering the targumist emphasizes the punishment meted out to those who sin. This, presumably, was intended to discourage the audience from any future disobedience. Such fiery rhetoric might have been best suited to the synagogal context.

Analysis

Finally, we must analyze the targum in order to determine how the targumist has modified the biblical text in order to convey or emphasize his message and address the questions of the date, provenance, and Sitz im Leben of our text. The analysis presented in Chapter 4 will attempt to determine the exegetical agenda of TgLam This analysis involves an examination of the methods employed by the targumist in translating the Book of Lamentations, including the targumist’s use of language (i.e., does the targumist use specific, theologically charged terms or phrases where other, simpler Aramaic terms would have sufficed), translation technique, and midrashic additions. In Chapter 5 we will attempt to determine the provenience and purpose of TgLam. We will begin with an examination of the language of the text, review rabbinic statements concerning the Book of Lamentations and its targum, and look for any references within the targum itself which might shed light on its origins and use within the community. This holistic analysis presupposes treating the targum as a single literary unit rather than as a mosaic of accreted traditions. This is not to ignore the evolutionary nature of targumic literature; rather it is a recognition that most of the texts which have been preserved took their form at the hands of a final redactor.