As a member of the Bible Gateway Blogger Grid #BibleGatewayPartner, I was offered the opportunity to review a free copy of The Evangelical Study Bible (Thomas Nelson Bibles, 2023; evangelicalstudybible.com). It is available for purchase from the FaithGateway Store and Amazon.

TLDR

“Too Long Didn’t Read,” as the kids say: The ESB does what it says on the cover. This is a study Bible written by and for Evangelicals. It has as its translation the New King James Version and features additional study aids, is printed in color, and has cross-references. It will not be a terribly useful aid for critical work, but it is not intended for such. It is a study Bible for Evangelicals and as such would make a lovely gift.

Evangelical

Now, to provide a bit more context and explication. This study Bible is an updated version of the 1988 Evangelical Study Bible commissioned by Jerry Falwell. Let’s take a step back, however to define “Evangelical” since that is central to then character and nature of this study Bible. The editors define “Evangelical” as … I don’t know because nowhere that I could find do they offer a definition. (It is a very large Bible, so perhaps it is in there somewhere.) I suppose, “IYKYK.” The most helpful clarify remarks on this subject come from the Foreward written by the late D. Edward E. Hindson (1944-2022), the General Editor of both editions of the ESB. “Each contributor is committed to the Evangelical Christian faith, based upon the inspiration and the inerrancy of the Bible.” Later, he reassures the reader that “each contributor is a born-again believer, with a deep personal commitment to Christ and belief in the inerrancy of Scripture.”

I make note of this because I grew up in a church and community that (and still does) identify itself as “Evangelical” and, while we debated the “inerrancy of Scripture,” it was not a fundamental tenet of that identity. I will note that the National Association of Evangelicals states that, as Evangelicals “We believe the Bible to be the inspired, the only infallible, authoritative Word of God.” For those outside of these debates there may not be a difference between “inerrant” and “infallible” but when I was engaged in such debates, there was an important if nuanced difference. “Inerrant” was taken to mean “without error in scientific or spiritual fact,” so the precise number of men able to go into war for Israel was 603,550 (Num. 1:46) and God created the world in precisely six days. “Infallible” was understood to mean “true in terms of teaching and doctrine,” leaving room for the idea that God created the world, but perhaps in a more expansive manner than depicted in the poetic Gen. 1. Of course, there was reasonable discussion around this points and I have not been deeply immersed in that world for many years now, so perhaps things have changed. Either way, for Dr. Hindson at last, a believe in inerrancy was a primary characteristic of “Evangelical” scholars.

Features

Returning to the ESB, if you are an Evangelical then I suspect that the ESB will indeed, as described on the flyleaf, “empower your convictions.” It certainly won’t challenge them, but that is beside the points since the ESB is unapologetically an Evangelical Study Bible. That is most clearly evident in one some of the innovations (aside from general updates) that set it apart from the prior Evangelical Study Bible. The “Dear Reader” essay highlights the four features that are unique to the ESB:

- Doctrinal Footnotes

- Personality Profiles

- Archaeological Sites

- Apologetics Articles

ESB, p. viii.

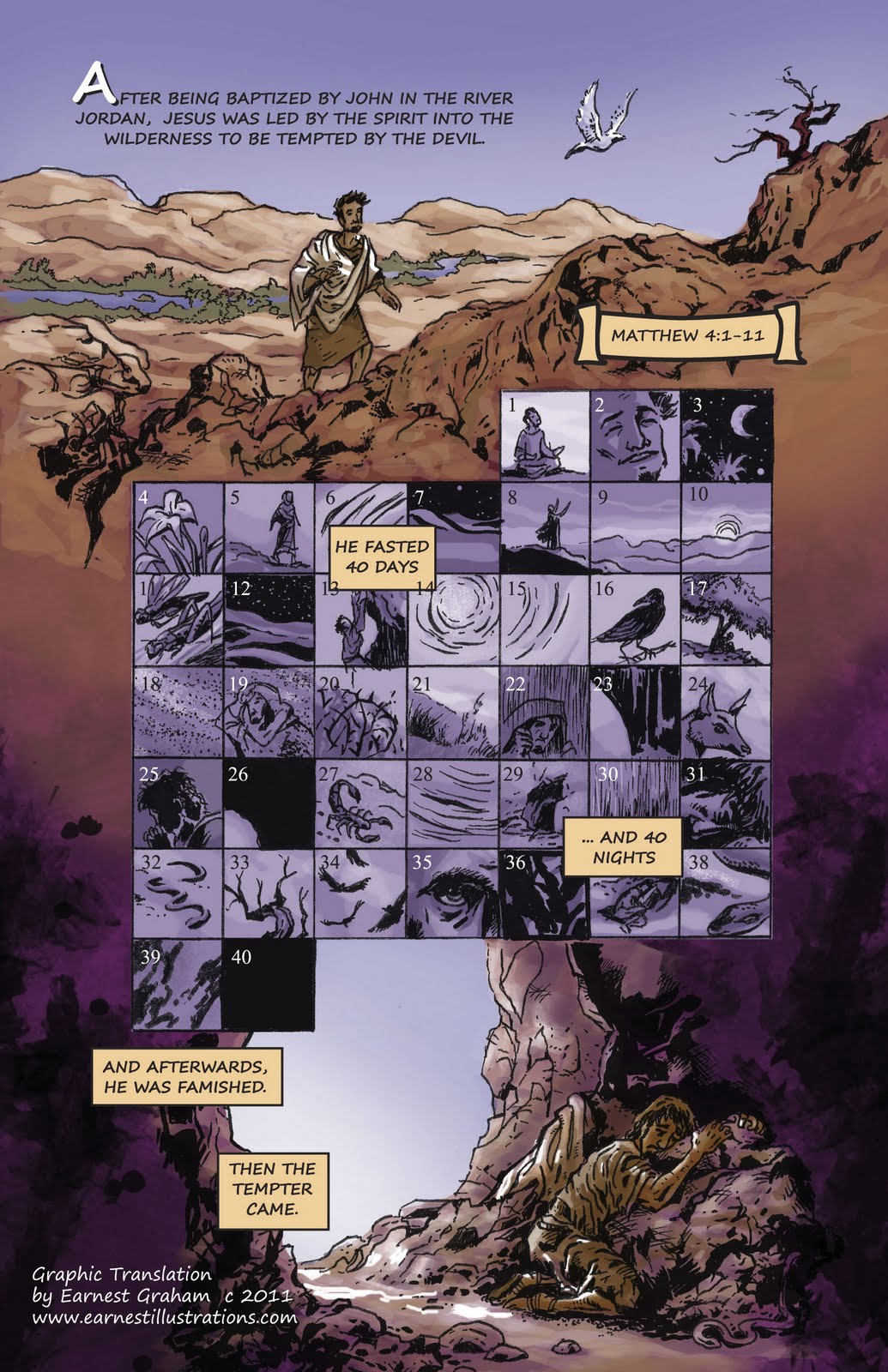

These are all very well done. The images, maps, and aids are often very colorful, clearly laid out, and the overall format of the ESB is conducive to reading and study. The sections describing the layout and how to use the ESB are very clear and helpful. There are no additional margins for note taking and the pages are quite thin, which some might find troublesome. (I suspect a highlighter or even a decent pen ink would go right through to the other side.) But back in the day, I would carry my NIV Study Bible in a carrier with a spiral notebook and pen inside, so I suspect that will not be a major set back.

The translation used in the New King James Version. I will not go into the issues and reason why I do not think that is an appropriate modern translation, but given the intended audience, that seems an appropriate choice. Certainly the Psalms are arguably more poetic in either the KJV or the NKJV than in most modern translations.

The content is often much more evenhanded and scholarly than the introduction (the ESB’s and mine) might give one to suppose. For example, the archeological note on Gen 12:10 “Historicity of the patriarchs” concedes that “the archaeological evidence for the patriarchs (second millennium BC) is not as well attested as it is for biblical peoples and events in the first millennium.” While there is the assumption of historicity and the 2nd millennium dating which indicates the a priori assumptions of the ESB, it is recognizing the paucity of physical evidence.

The images found throughout the ESB are very nice, well printed, (“Printed in China”), and cited. The center column cross-references remind me of my old Thompson’s Chain Reference. The “Doctrinal Footnotes” and “Apologetics Articles” are obviously the main areas where their theological comments come forward. Again, I would question whether all those who call themselves “Evangelical” would agree with the assertions in the notes, but that is for others to critique. To give a sense of their notes, for example, “Virgin Birth” is addressed at Luke 1:21. The basics of the doctrine are put forth then we have an “Illustration” and an “Application.” The “Illustration” is telling: “Those who deny the virgin birth tend also to deny His deity, so they must necessarily question the integrity of the Scriptures.” (Emphasis mine.)

There are a couple of odd things I noticed in examining the commentary portions. I found it odd that the”Introduction to the Old Testament” is two pages while the “Introduction to the New Testament” is 2 and a half. I realize that every book receives detailed explication, but some broader canonical contextualization of the two Testaments would have seemed in order and, given the expansive size of the OT compared with the NT, a bit more balance. I was relieved to read that, unlike my Thompson Chain Reference referenced earlier and which cited the time between testaments as “The Silent Years,” the ESB states that although they are “frequently described as ‘silent,’ but they were, in fact, crowded with activity.”

One small, final note. It is oddly yet deeply frustrating that the title of this volume lacks the definitive article. It is not “The Evangelical Study Bible” but “Evangelical Study Bible.” It simply feels grammatically incorrect. You will have noted that I simply referred to it as “the ESB” in this review. That was my cognitive compromise.

Verdict

Already stated above, for the audience intended this is a very nice study Bible, in execution and material provided. I suspect it would prove frustrating for those who would like more critical discussion of the historical, textual, and theological concerns, but there are other commentaries and study Bibles for those readers. I know of a lovely friend who will be happy to receive my copy as a gift and will “read it, memorize it, and meditate on its truths,” just as Dr. Hindson intended.

Images

2 thoughts on “Review: Evangelical Study Bible”

“The translation used in the New King James Version. I will not go into the issues and reason why I do not think that is an appropriate modern translation, but given the intended audience, that seems an appropriate choice. Certainly the Psalms are arguably more poetic in either the KJV or the NKJV than in most modern “

Do you have a favorite translation? NRSV? I generally use the ESV and virtually never the “old” KJV. I do use the NKJV because everyone in the room except my wife uses the “old” King James. It is easier for them to follow along in their Bibles. Wife uses NIV.

Anything you want to write about the poetry I would love to read. I talk about it and read from it a lot at church. That’s one thing I don’t like about the KJV. I’ve never seen a copy that formats the poetry in poetical form. The parallelism needs to jump off the page. It doesn’t in KJ. You have to figure it out which is problematic with an unskilled person.

John, it is good to hear from you again. I always hesitate to say what is a “favorite translation” because all translation is compromise (we learn this best of all by doing our own translations). I use NRSV for several reasons: (1) It is more-or-less the default now for scholarly work, unless one is providing their own translations or using JPS. (2) It makes use of the best text editions that we have to date and usually provides footnotes to indicate translational choices (e.g., where “brother” is rendered as “brother and sister.” (3) It is the primary translation for the Episcopal Church, where I am most often teaching and preaching, outside of the university. It is NOT always consistent throughout the works, however. Going from memory, in Galatians, within a few verses, there are 3 different renderings of “brother.” That is not good translation practice, in my opinion. You should find an equivalence and stick to it, unless the context requires a different rendering.

Regarding poetry, I was simply referring to the fact that I think older English forms, to my “ear,” are more elegant in the poetic context. That does not mean that it actually renders the Hebrew in a better form. In fact, I quite like the translation in the Book of Common Prayer (USA). There is an engaging little book on these translations. It is based upon the Coverdale but with updates/revisions. Auden, the Psalms, and Me. Some aspects of its development are appalling to my academic sense (Auden and other poets “altered” the Hebrew scholars’ translations to make it “better” English), but I cannot deny it both keeps the parallelism of the Hebrew and is often graceful English.