The selection below was written “on background” one might say. I wanted to articulate what I thought was a close and “simple” reading of how the Book of Ruth presents the character of Boaz. I then went on to critique a few key modern interpreters, but that will have to wait for another post or even a published article. (We shall see.) In the meantime I thought it might be worthwhile to post this “First Reading” and solicit feedback.

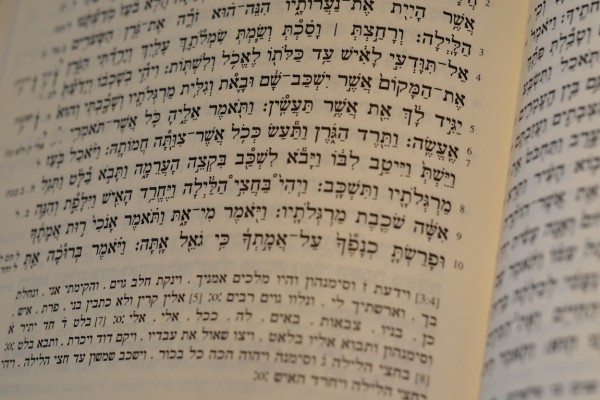

Who is Boaz in the Book of Ruth?

It is often and reasonably said that there can never be a “simple” reading of a text. No matter how conscious we are of ourselves, our culture and influences, we cannot simply read the text on its own terms. Perhaps, but certainly some readings are more likely than others, more firmly grounded in the text itself and less in our own inferences and intuition. This exercise is part of a larger project to consider how the Targumist has adapted, interpreted, and transformed the book of Ruth in the process of producing Targum Ruth (TgRuth). In order to understand the Targum we must first have a firm understanding of the text upon which it is based, attempting, in so far as we are able, to set aside the interpretive accretions of millennia and see the biblical text on its own terms. That is what I have tried to do with respect to the figure of Boaz.[1]

The biblical account

The book of Ruth presents Boaz as a figure who is vital to the plot; he is necessary for the preservation of Ruth and Naomi. The biblical narrator makes it clear in a number of ways that Boaz is primarily a tool used and manipulated by the women, with very little value of his own aside from his role as redeemer. Boaz is centrally marginalized. He is a key member of the cast and the only principle male yet he is marginalized, pushed to the edges such that his actions are reactions. His function in the plot is necessary yet contingent upon the two women about whom this story revolves.

The four chapters of the book of Ruth are often and understandably broken down into four primary scenes with actions attributed to different characters in each. In chapter 1 it is Naomi who is the primary mover, returning to Bethlehem and setting off the chain of events about which the book is concerned. Ruth becomes the active agent in chapter 2 as she takes charge of the situation and sets out to provide sustenance. Chapter 3 is most often depicted as belonging to Naomi, for although Ruth is the one who must go out to the threshing floor to confront Boaz, it is Naomi who lays out the plan for her daughter-in-law. Finally, in chapter 4 the action undoubtedly belongs to Boaz.

Chapter One

While it is true that Elimelech is mentioned before Naomi in the opening verses of the book, by the third verse he has become “the husband of Naomi.” The narrative certainly implies that it was the decision of the husband to leave Bethlehem to go to the fields of Moab yet neither he nor his sons ever speak. The primary function of the Elimelech and his sons is, bluntly put, to die and thus bring about the crisis upon which the book is based. It is at this point, with the husbands now deceased, that the story really begins and “she” becomes the subject.

“Then she started to return with her daughters-in-law from the country of Moab.”[2] It is Naomi, by her return to Judah and urging of her daughters-in-law to remain in Moab, who precipitates Ruth’s decision to leave her own home and gods to remain with her mother-in-law.[3] The first chapter focuses our attention to the plight of these women, themselves representing two of the most vulnerable classes of people, both of them widows and one a foreigner. The men, who were the driving force in the opening two verses of the book, are all dead by the fifth. Again turning to Trible who summarizes it so succinctly: “The males die; they are nonpersons; their presence in the story ceases…. The females live; they are persons; their presence in the story continues. Indeed, their life is the life of the story.”[4]

The chapter concludes with the famous declaration by Ruth of her loyalty to Naomi. While some consider this to be Ruth’s religious “conversion,” Ruth’s unequivocal statement to her mother-in-law is that she remain with Naomi until death.[5] Linafelt has noted that both Ruth and Naomi’s speech is in the form of poetry, setting their words aside from the rest of the narrative and bringing the first chapter to a conclusion with a clear focus upon these two women as the primary characters of the book. Boaz, in contrast, “is confirmed on this reading as secondary to these two women.”[6] The chapter concludes with the two women headed to Bethlehem “at the beginning of the barley harvest.” The famine has been lifted from the land, but it has fallen upon Naomi and her daughter-in-law who is, we are reminded, “the Moabite.”

Chapter Two

In chapter 2 we finally meet Boaz. The audience is made aware of him even before Ruth knows of his existence. Naomi, even as she is encouraging her daughters-in-law to return to their mother’s house in hopes that they will “find security…in the house of your husband” (Ruth 1:9), never spoke of finding a man to help herself. She does not seem to consider the possibility of a male redeemer or, if she does, such is not revealed to the reader. It is the narrator who mentions Boaz and only to prepare the audience for his entrance.[7] When he does step onto the stage it is only after Ruth has taken the initiative to go out into the fields to find food for herself and Naomi.

The narrator introduces Boaz by telling us that he is אִישׁ גִּבּוֹר, a “great man,”[8]and yet this great man (whether in terms of power or of merit)[9] only reacts to the initiative of Ruth; it is her audacious presence that leads him to inquire about her. His speech to Ruth makes it clear that he knew of Naomi’s return from Moab and of Ruth’s faithfulness to her, “All that you have done for your mother-in-law since the death of your husband has been fully told me.” Yet for some reason he never sought out Naomi or Ruth until she was before him, then he had to take notice. Many commentators have spent a considerable amount of effort wondering why Boaz did not seek out Naomi before this moment and what his motivation would be in caring for Ruth now.

It is notoriously difficult to attempt to discern an author’s intent. I would suggest that it is even more foolhardy to attempt to discern a character’s motivation without some clear indication from the text itself. Campbell offers these provocative words on this subject:

It is inherent in biblical thought generally that a person’s actions and words offer a true picture of the person’s character. Hebrew stories do not have characters with hidden motives and concealed agendas, or if they do, the audience is explicitly told about it.[10]

Certainly biblical characters are often devious and do have agendas and perhaps Campbell is right in saying that when they do the audience is allowed into the conspiracy.[11] In the case of Boaz what we find is what the character is. We could make up a back story (which, as we shall see, is precisely what the rabbinic sources have done) and provide him with motives for not engaging with Naomi or Ruth before this moment. Or we could accept that Boaz does not enter into the story prior to this point because the author intended it to be this way, he had no use for Boaz until this time in the story. His character is marginal, he only makes an appearance on the stage when necessary, and he does not initiate anything but rather reacts to Ruth’s decisions and actions.

The fact that Boaz remains in reserve and is more reactive than proactive does not mean that his character is without qualities that can be discerned from the text. When he arrives at his fields he greets his workers with the name of God, “The Lord be with you” (Ruth 2:4). This is the first of two blessings that Boaz will offer in this chapter in the name of the Lord (Ruth 2:4 and 2:12). Most modern commentators understand his initial greeting to the workers as a simple, conventional greeting.[12] Linafelt’s suggestion that Campbell and Nielsen view this greeting as “an indication of [Boaz’s] great piety or moral character” seems to overstate their arguments.[13] What those commentators have rightly done is consider this initial, customary greeting in combination with Boaz’s blessing of Ruth. Taken together, these invocations of the name of God and particularly that the latter appears to be a genuine petition from Boaz to God in light of Ruth’s own faithfulness[14] an image of Boaz emerges of a man who, in words at least, views the Lord as central to the blessing and survival of his people.

We cannot speak to Boaz’s “devotion” beyond this, however, since the narrator does not provide us with additional insights into what today we might call his theological convictions. We should, however, consider his actions even as he considers and praises Ruth’s actions towards her mother-in-law. Once Boaz has been introduced into the narrative and the character becomes aware of Ruth he immediately begins to take steps that would ensure her and Naomi’s well-being. I have already commented on the inadvisability of seeking to determine a character’s motivation when the narrator does not provide us with any information about such matters and we will return to this matter below in considering Fewell and Gunn’s arguments.

Linafelt makes an important point by noting that Ruth herself questions Boaz as to why he should treat her so well (Ruth 2:10). “Her question is not just (or perhaps even) a show of gratitude, but a genuine question probing his motivations for showing her ‘favor’ and for singling her out for ‘attention.’”[15] Linafelt is not, however, satisfied with Boaz’s response and reads his invocation of the Lord as efforts to deflect his real interest: Ruth.[16] While there is some implicit sexual tension here there is nothing in the text to suggest that his initial actions are anything other than stated: a response to her own hesed towards Naomi. This is not to say that he is not interested in Ruth at all. He calls Ruth over to him at mealtime and even prepares her food (Ruth 2:14). Boaz then directs his men to ensure that she will have plenty of food, allowing her to glean far beyond what the law stipulates. Clearly Ruth has caught his attention.

By the time she returns home to Naomi Ruth has some sense of who Boaz is and that he shown interest in her. What she does not yet know, but which the audience does, is that he is a kinsman to Naomi and is a “great man.” In the field he demonstrated that his custom and worldview includes invoking of the name of the Lord that he might bless those who show kindness to others. He too has shown kindness to Ruth (and perhaps a bit more as well) as he makes arrangements for her protection and provision while gleaning for food for herself and Naomi. While I would not claim, on the basis of the text thus far, that Boaz is clearly a main of great piety and devotion,[17] it does seem that the narrator has presented us with a figure who is a good man.

Chapter Three

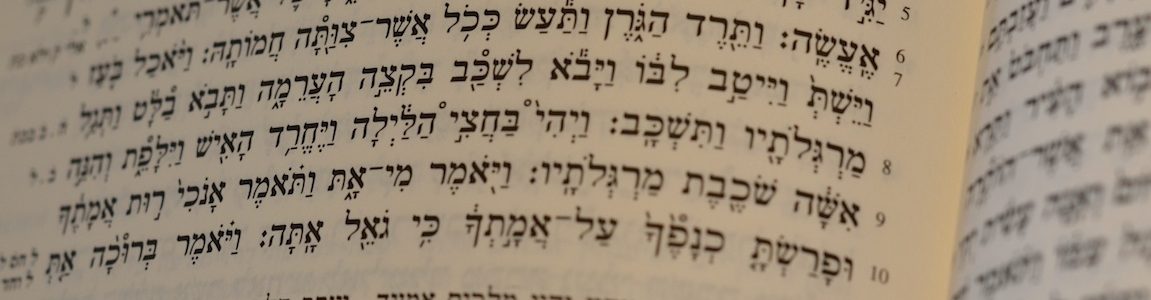

Chapter 3 is often viewed as Naomi’s since it opens with Naomi taking responsibility for Ruth’s well-being (“I need to seek some security for you, so that it may be well with you”) and offering a plan for Ruth to present herself to Boaz. On the other hand, it is Ruth who not only acts out that plan but, as many have noted, goes beyond Naomi’s instructions.[18]The opening verse of chapter 3 also indicates that our attention should now be focused upon Ruth rather than Naomi since the latter is described in reference to the former (“Naomi her mother-in-law”). Whether we view Naomi or Ruth as our primary mover in chapter 3 Boaz is simply left to react to the decisions made by the women.

When Boaz does awake in the middle of the night Ruth identifies herself and rather than waiting for direction from the man, tells him directly what must be done. “I am Ruth, your servant; spread your cloak over your servant, for you are next-of-kin” (Ruth 3:9). Once again, while we could speculate as to what Boaz might have said if Ruth had not given him direction, we need to consider his words and actions as provided by the narrator. His first words are to invoke the Lord’s blessing on her because of her hesed.[19] While some find this to be feigned piety (see below) others accept this as a genuine aspect of the character of Boaz. I am inclined to view him as a complex figure with good intentions and a firm grasp of the real social situation confronting him.

The fact that Boaz seems to praise or affirm her request for marriage has struck some as odd. “This last instance of your loyalty is better than the first; you have not gone after young men, whether poor or rich” (Ruth 4:10). Sasson asked rhetorically, “How could one not find fault with a man who chooses to value a marriage proposal over an act of mercy?”[20] But while the question of whether or not the union between Boaz and Ruth is levirate marriage is beyond the scope of this article it does influence how one perceives this passage and Boaz’s response to Ruth. The problem is a difficult one,[21] but given the manner in which the story progresses with chapter 4 it seems reasonable to conclude with Campbell, “Ruth’s presupposition that the responsibilities of redemption and marriage belong together is accepted by all as the story progresses.”[22]

In all of this discussion it is important not to lose sight of the fact that Ruth is driving the plot, not Boaz. Whether the issues of levirate marriage and redemption are distinct or unified does not matter. Ruth has come to Boaz and forced him to take action, something he has not done in the several months that Ruth and Naomi have been back in Bethlehem. He responds in a positive and decisive manner. He blesses Ruth and promises that he will take care of the matter on the very next day. He even sends her home with an extraordinary amount of grain, a sign, if nothing else, of his commitment to her and concern for the continued well-being of Ruth and Naomi. Without access to the character’s thoughts and motivations to inform us otherwise, in chapter 3 we find that the figure of Boaz continues to emerge as a decent man, cautious perhaps, but when confronted with a choice he does and even goes beyond what is considered culturally proper.[23]

Chapter Four

The final chapter is often, of course, considered Boaz’s since it is primarily concerned with his actions at the city gate, his “taking” Ruth as his wife, and the subsequent conception and birth of Obed. The activity of chapter 4 is, as so many have noted, very much a male world.[24] The actions all move quickly and succinctly. Boaz has taken charge and, as Naomi assured Ruth, did not rest until he had settled the matter. The details and historicity of the events described in chapter 4 have been widely debated. Campbell takes the pragmatic approach and urges interpreters to “approach the scene with the expectation that things should make sense, in spite of the ocean of ink which has been spilled over a number of unanswered questions raised by the scene.”[25] There are very real issues raised in chapter 4, but for the purpose of considering the character of Boaz we may follow Campbell’s advice.

Chapter four opens with immediacy. Within first few words Boaz has arrived at the city gate and already begun his business with “So-and-so” (פְּלֹנִי אַלְמֹנִי). Then, after some formalities and blessings, “Boaz took Ruth and she became his wife.” The events move swiftly and Boaz deftly maneuvers the negotiations so that they reach a satisfactory conclusion. He has done all that he has promised to Ruth and the result is marriage, offspring, and the perpetuation of the name of the deceased (and of course the assurance of the ultimate birth of King David).

This all occurs in the realm of men. There are no women among the elders and in fact we do not hear from Ruth or Naomi again in the story. The only women who are given speech are the women of the community (Ruth 4:14-15, 17).[26] These same women were so startled at the state of Naomi upon her return to Bethlehem that they exclaimed, “Is this Naomi?” Now they conclude the story of Naomi’s restoration by declaring, “Blessed be the Lord, who has not left you this day without next-of-kin; and may his name be renowned in Israel!” After praising God, however, they remind everyone that the agent of this deliverance was Ruth, “for your daughter-in-law who loves you, who is more to you than seven sons, has borne him.” Although our two main female characters are silent, the author has driven home the point that this is their story and it has come about because they drove the plot.

The swift and decisive action by Boaz at the city gate would not have occurred if not for Ruth confronting him with the demand: “Spread your cloak over your servant, for you are next-of-kin.” Even when it seems, as some might argue, that this incredible story of women’s initiative is undermined at the very end by the silencing of our main characters and Boaz’s emergence into center stage, the primary mover of these events remains Ruth. Furthermore the very end of the story once again belongs to the Naomi and Ruth as the women of the community step forward and bless Naomi and even name the child, “A son has been born to Naomi.”[27]

There is no doubt that Boaz is a key player in the book of Ruth; without the male redeemer safety and security for Naomi and Ruth could not be ensured. But Boaz’s engagement is restricted to reacting to Ruth’s actions and directions. It is worth taking a moment to remind ourselves of how revolutionary this work would have seemed to its original audience. There are certain tropes and themes to be expected, Boaz is certainly presented as a very good man, invoking the name of the Lord in blessing and seeking to provide for Ruth and Naomi when the chance is presented to him. However it is the women, and more specifically the foreign woman Ruth, who direct the action. As a character Boaz has more in common with Rachel or Leah than Jacob; he has certain key moments of dialogue that move the plot, but ultimately his primary function is to provide security and offspring.

[1] Of course there are many who have done similar studies and their work will be noted throughout.

[2] All biblical translations are from the New Revised Standard Version (Oxford: OUP, 1989) unless otherwise noted.

[3] I do believe that throughout the book it is, in fact, Ruth who is our primary mover. She is insistent with Naomi that she remain and, as I will explain above, it is she who drives the story from chapter 2 onward.

[4] {Trible 1982@168-9}.

[5] I have considered Ruth’s conversion in a paper presented at the 2008 Aramaic Studies session of the Society of Biblical Literature’s annual convention. An article is forthcoming, but it is worth noting here that the rabbinic sources depict Ruth as the proselyte par excellence.

[6] {Linafelt 2010@127}.

[7] It is worth noting with Bush that Boaz’s identity is given in relation to Naomi; “Naomi had a kinsman on her husband’s side,” {Bush 1996@49}.

[8] See {Hubbard 1989@90}. The term is much debated and variously translated: “a mighty man of wealth” in the KJV, “a prominent rich man” in the NRSV, “a man of substance” in JPS, and “a man of standing” in the NIV. As Hubbard points out, “The translation ‘man of substance’ has just the right ambiguity to cover the term in Hebrew.”

[9] See below for the Targumist’s treatment of this phrase.

[10] {Campbell 1975@112}. Linafelt states this in a slightly different way, “in biblical narrative, we are only rarely told what a character might be thinking or feeling at any given moment,” {Linafelt 2010@120}.

[11] But I am far from convinced that this is “generally” true or that the audience is always, explicitly told about the motivations all biblical characters.

[12] See, for example, {Hubbard 1989@144} particularly notes 14 and 15, {Nielsen 1997@57}, and {Campbell 1975@112}.

[13] {Linafelt 1999@29}.

[14] “May the LORD reward you for your deeds, and may you have a full reward from the LORD, the God of Israel, under whose wings you have come for refuge” (Ruth 2:12).

[15] {Linafelt 1999@36}.

[16] For example, Linafelt suggests that Boaz “seems to be intent on playing the pious, disinterested father-figure” {Linafelt 1999@36-7} (emphasis is mine). This is Linafelt’s reading into Boaz’s motivation rather than allowing the text to stand as read.

[17] See, for example, {LaCocque 2004@65}.

[18] Ruth 3:4, Naomi says, “go and uncover [Boaz’s] feet and lie down; and he will tell you what to do.” When the time comes Ruth, in fact, tells Boaz what to do. See {Trible 1982@184} and {Linafelt 1999@51}.

[19] While there is disagreement as to what, if any, is the single theme of Ruth (see {Hubbard 1989@35ff}) almost all commentators, ancient and modern, rightly note that hesed is a strong theme of the Book of Ruth. See, for example, {Campbell 1975b@29-30}, {Nielsen 1997@31}, and RuthR 2:14.

[20] {Sasson 1978@55}. Linafelt ({Linafelt 1999@57}) incorrectly cites Sasson, both by citing the wrong article and implying that this was Sasson’s reading of Ruth 4:10. Sasson, in fact, believed quite the opposite. “Boaz singles out her unselfish attempt at finding a go’el to resolve her mother-in-law’s difficulty as worthier than her self-serving hope to acquire a husband,” {Sasson 1978}.

[21] See {Hubbard 1989@48ff}, {Carmichael 1977}, and works cited therein.

[22] {Campbell 1975@132}. Fewell and Gunn, as we shall see, take a very different view and while Linafelt is doubtful of Campbell’s interpretation he remains cautious in his conclusions {Linafelt 1999@58ff}.

[23] See below for further discussion about what would have been culturally permissible for a man in Boaz’s position. He could have, presumably, simply taken Ruth for himself if he had wanted, without going through the machinations associated with levirate marriage and redeeming the land.

[24] “This public gathering is entirely a man’s world,” {Trible 1982@188}. Trible also tells us that it is in scene four that “Boaz takes charge.” As I shall argue, he only steps into that role after being pushed by Ruth. See also {Meyers 1999}.

[25] {Campbell 1975@154}

[26] It is possible, even likely, that women are also included in the statement of witnesses in Ruth 4:9 since the text specifies it is “the elders and all the people.”

[27] {Trible 1982@196}, “The women of Bethlehem do not permit this transformation [man’s world, etc.] to prevail. They reinterpret the language of a man’s world to preserve the integrity of a woman’s story.”

4 thoughts on “Boaz – A close reading of Ruth”

I recently was reminded that the book of Ruth presents Rahab, the prostitute, as being the mother of Boaz. I understand that there may be some generations between that are not mentioned, but does anyone talk about how having Rahab as an ancestor might have influenced or affected Boaz? It seems to me that being the child of a known prostitute and foreigner, irrelevant of how much she had helped Israel in the past, would cause someone to be more on the outskirts of society and perhaps even more open to (other) foreigners.

Brenda – It is interesting you should mention that. It is NOT found in the book of Ruth itself, rather it is an attribution found in the genealogy in Matt. 1:5.

I do not recall ever reading any commentator on the book of Ruth bring this out as a possible motivating factor in Boaz’ character. Of course, most scholars working in that vein also do not attribute great historicity to Boaz, let alone to the genealogical details, particularly those found in the NT, so they would be less likely to consider such an approach. Still, even among conservative Jewish and Christian authors I do not recall reading anything considering this angle.