This was a paper originally presented at the Mid-Atlantic SBL in 2010 and was going to be part of an article on the character of Boaz. Now that the book on Tg. Ruth is complete, this will not be making it into an article and so I thought I would make it available here. You can find a companion “close reading” of the character of Boaz that I posted two years ago here. NB: Citations did not make it over in the copy-paste process, but I have placed a select bibliography at the end that contains the works cited (plus a few more relevant works). An earlier version of this with footnotes and audio from the presentation can be found here.

Boaz: Centrally Marginalized

Ruth and Naomi are rightly understood by most commentators as the central figures of the book of Ruth and most agree that Ruth and Naomi are the initiators of all action and Boaz merely the respondent. As Phyllis Trible noted, “Boaz is the reactor to their initiative.” Thus in many ways Boaz is only marginally relevant to the story, he is present because only a male figure could accomplish the deeds necessary to secure Ruth and Naomi’s future.

Yet there has been a tremendous amount of attention paid to Boaz over the centuries. Older and more traditional commentaries, going back to the rabbinic sources and as recent as, for example, Frederic Bush, depict Boaz as the righteous and benevolent savior of Ruth and Naomi, often to the extent that the women are displaced from their central roles. More recently, however, we find commentators like Fewell and Gunn who focus upon Boaz precisely with the purpose of diminishing his role in some way.

Boaz has thus been centrally marginalized in two instances. In the first case by the narrator since the story itself places Boaz in a distinctly tertiary role relative to Ruth and Naomi, and in the second case by the scholars who seek to reduce his actions to those of a horny old man.

The Biblical Account

The biblical story itself presents Boaz as a figure who is key to the plot. He is a necessary element of the preservation of Ruth and Naomi, but it is made clear in a number of ways that he is merely a tool, used and manipulated by the women, with very little value of his own aside from his role as “redeemer.”

The four chapters of the book of Ruth are often and understandably broken down into four primary scenes with actions attributed to different characters in each case. In chapter 1 it is Naomi who is the primary mover, first leaving Bethlehem and then returning. It is Naomi, by her return to Judah and urging of her daughters-in-law to remain in Moab, who precipitates Ruth’s decision to leave her own home and gods to remain with her mother-in-law. In chapter 2 we find Ruth taking the initiative, going out to provide for their sustenance. Chapter 3 is often viewed as Naomi’s since although Ruth is the one who must approach Boaz in the dark of the night, it is Naomi who provides her with the counsel and guidance. The final chapter is, of course, considered Boaz’s since it is primarily concerned with his actions at the city gate and his “taking” Ruth as his wife and the subsequent conception and birth of Obed. Chapter 4 is, as so many have noted, very much a male world (Trible).

While such a description and breakdown of the book of Ruth is reasonable, it obscures the fact that it is Ruth who is actually the instigator of all central actions. It is Ruth’s passionate insistence on staying with Naomi that sets the stage for everything that follows and it is of course Ruth who takes the initiative to go and glean for their sustenance. While chapter 3 opens with Naomi taking responsibility for Ruth’s wellbeing (“I need to seek some security for you, so that it may be well with you.”) and offering a plan for presenting herself to Boaz, it is Ruth who not only acts out that plan but, as many have noted, goes beyond Naomi’s instructions. The events of chapter 4 thus come about because Ruth took the initiative and moved Boaz into action. It is true that Ruth does not speak again in the story after she reports back to Naomi the events of the night at the threshing floor, but it is her words to Boaz that are the motivation behind every action of chapter 4. Boaz is acting precisely because Ruth did not wait for Baoz to tell her what to do, but rather she told him “spread your cloak over your servant.”

The figure of Boaz, on the other hand, has an important and yet marginal role in the story. In chapter 2, for example, when Boaz finally appears on the scene he acts, but only in response to Ruth’s presence. His speech makes it clear that he knew of Naomi’s return from Moab and Ruth’s faithfulness to her, “All that you have done for your mother-in-law since the death of your husband has been fully told me.” Yet for some reason he never sought out Naomi or Ruth until she was before him and he had to take notice. Many commentators have spent a considerable amount of effort wondering why Boaz did not seek out Naomi and what his motivation would be in caring for Ruth now. I will deal with the latter below, but a few words about the former are appropriate here.

We all know how notoriously difficult and even dangerous it is to attempt to discern an author’s intent; I would suggest that it is even more foolhardy to attempt to discern a character’s motivation without some clear indication from the text itself. I am still not sure if I completely agree with Campbell’s following statement, but there is certainly truth within it.

It is inherent in biblical thought generally that a person’s actions and words offer a true picture of the person’s character. Hebrew stories do not have characters with hidden motives and concealed agendas, or if they do, the audience is explicitly told about it.

Certainly biblical characters are often devious and do have agendas and perhaps Campbell is right in saying that when they do the audience is always allowed into the conspiracy. With the case of Boaz I think that what we find is what the character is. We could make up a back story (as the rabbis do) and provide him with motives for not engaging with Naomi or Ruth before this moment. Or we could accept that the author had no use for Boaz until this time in the story. His character is marginal, he only makes an appearance on the stage when necessary, and he does not initiate anything, but rather reacts to Ruth’s decisions and actions.

Chapter 4 is, as noted already, often considered Boaz’s chapter and it is certainly primarily concerned with his actions. Boaz goes to the city gate and settles the business with “So-and-so” (פְּלֹנִי אַלְמֹנִי) and then after some formalities and blessings “Boaz took Ruth and she became his wife.” This all occurs in the realm of men. There are no women among the elders and in fact we do not hear from Ruth or Naomi again in the story. Yet all of this occurred because Ruth directed Boaz saying, “spread your cloak over your servant, for you are next-of-kin.” Even when it seems, as some might argue, that this incredible story of women’s initiative is undermined at the very end by the silencing of our main characters and Boaz’s emergence into center stage, the primary mover of these events remains Ruth. Furthermore the very end of the story once again belongs to the women as the women of the community step forward and bless Naomi and even name the child, “A son has been born to Naomi.”

There is no doubt that Boaz is a key player in the book of Ruth; without the male redeemer safety and security for Naomi and Ruth could not be ensured. But Boaz’s engagement is restricted to reacting to Ruth’s actions and directions. It is worth taking a moment to remind ourselves of how revolutionary this work would have seemed to its original audience. There are certain tropes and themes to be expected, Boaz is certainly presented as the pious patriarch, however it is the women, and more specifically the foreign woman Ruth, who are in complete control. As a character Boaz has more in common with Rachel or Leah than Jacob; he has certain key moments of dialogue that move the plot, but his primary function is to provide offspring.

[Addendum: Jim Getz, one of our colleagues who was here last night but has since returned to Philadelphia just commented on my blog this morning. I think his comment is worth sharing. “Could the antiquated language of Boaz (his use of paragogic nun’s) be a very tangible representation of this marginalization by the narrator? The very way he speaks is distinct from the other characters in the story. He’s in some way marginalized every time he opens his mouth.”]

Modern marginalization

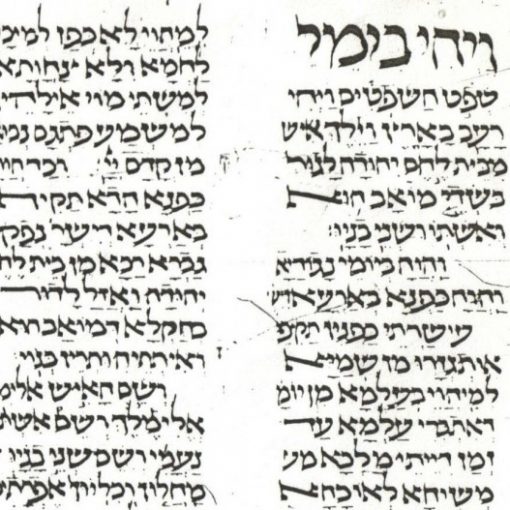

If the biblical text has reserved the spotlight for Ruth, most commentators up until the last century have widened the spotlight to make room for Boaz, in some cases eclipsing the women altogether. For example, in the Targum to Ruth Boaz is not only a pious man, he is a scholar of Torah and a prophet. In reaction to such interpretations and following the general societal changes in the last 50 years or so scholars have rightly begun to refocus upon Ruth and Naomi. At the same time some have sought to diminish the role of Boaz. I want to consider briefly one such theme of marginalization found in contemporary scholarship, that of portraying Boaz as nothing more than a horny old git, who reacts primarily to his primal urges rather than out of any altruistic or religious motives.

Fewell and Gunn present this argument in their 1989 article “Boaz, Pillar Of Society” and later develop it in their book Compromising Redemption. They begin by asking “what is the nature of Boaz’s interest in Ruth?” and conclude that “for all his piety and generosity, for all his acclaimed responsible behavior, his desire for Ruth cannot be cloaked. His last, and most telling, move is to have sexual intercourse with ‘this woman’ (4.13).” Others have since accepted this view or some modified version of it. The result of such a reading is that while Boaz’s actions are important for the movement and culmination of the story, his character is impugned and his motives are reduced to physical impulse.

While I have just argued that Boaz’s character is marginal, I do not find this reading plausible for several reasons. The fundamental flaw is with Fewell and Gunn’s attempt to read beneath the text, looking for Boaz’s motives. I have already commented that such an effort is foolhardy since we only have at our disposal what the text provides and in this case, that is not very much. As Tod Linafelt notes in his commentary concerning the fact that Boaz’s first question to his men is about “this young woman,” “As always, the narrator give [sic] us no glimpse into Boaz’s thoughts, so the motivation behind his interest is left up to the reader to decide.”

As almost every commentator notes, chapters 2 and 3 are full of sexual tension and innuendo. This certainly would serve to titillate the audience and maintain their interest, but these hints and double entendres are hardly indicative of a scheming Boaz who is eager to have this foreign women for himself. I want to be clear, I am not trying to make Boaz a moral paragon, although I do think that his invocations of the Lord cannot be set aside as mere convention, as a marginal character I think that Boaz is as the author has presented him.

Boaz is clearly older than Ruth and his instructions to his men and assurances to Ruth that they will not bother her, speak more of paternalistic concern than piety or prurience. That is why, as Tod has noted, Boaz’s response to Ruth’s forthright and even aggressive request that he spread his cloak over her is full of fluster and bluster. The very thought that she should have considered him a possible mate has rattled him. If that is the case then it is hardly likely that he had been fantasizing about her as F&G imagine.

In commenting on chapter 3 and 4 Fewell and Gunn discuss Boaz’s concern for propriety. Following the dialogue with Ruth at the threshing floor F&G comment

What is veiled at this point is [Boaz’s] concern for himself and his standing in the community.

They go on to argue that Boaz is more concerned with preserving his reputation and satisfying his sexual desires for Ruth than he is for the redemption of Naomi’s property and fulfilling levirate duties. I think there is little doubt that Boaz’s actions sending Ruth home early in the morning and seeking to quickly settle matters with So-and-so, are all intended to formalize their relationship in a manner that would be acceptable to the community.

But if, as Fewell and Gunn argue, Boaz’s primary motivation throughout the story is to satisfy his sexual desire for Ruth why would he go to all of this trouble? Surely a prominent man like Boaz could take Ruth if he wanted without worrying about the consequences for himself. She is a Moabite, a foreigner, and as was discussed in a paper yesterday, a man could take any woman he wanted, so long as she was not already belonging in some way to another man. Gen. 38 and the story of Tamar and Judah is often and for good reason brought into the discussion of Ruth. The comparison is apt in this specific instance, since Judah’s sin was not in taking a prostitute, it was in not providing his son for the purpose of fulfilling his levirate duties. If propriety is Boaz’s concern then he could have taken Ruth at any time he pleased. I think instead his hesitancy and his actions can be better explained as his concern for Ruth and her status and image within the community.

Fewell and Gunn go on to explain that the whole point of the public confrontation with So-and-so was to create a situation where this otherwise dubious relationship with the Moabite woman becomes the mark of a virtuous man.

All this is in the interests of raising up the name (fame and honor!) of the dead man to his inheritance (and notice that these are the terms in which the matter is put—and precisely not in terms of helping the poor and needy, especially the widow, etc., which is what many critics are so anxious to see here). The patriarchy loves it. What nobler end could one strive for, make sacrifice for? All hail to Boaz! All hail to the man who for the sake of his brothers, living and dead, would marry a Moabite woman!

I want to note that Fewell and Gunn make many important observations in their study, not least of which is to criticize those who would provided motives to Boaz that are pure and pious, but the net result, perhaps unintended, is that they have elevated Boaz into a position of prominence far beyond that presented by the author. Through their own creative act of imagining Boaz’s motivations and machinations Fewell and Gunn have created a separate story where this wealthy man, concerned for his own social standing and personal needs drives the events to an end that meets the fulfillment of his desires.

Such a re-creation might be possible if we are considering an historic event with multiple reports and sources. But even if what lies behind the book of Ruth are actual historical figures what we have before us today is a piece of literature, carefully crafted in a particular way with particularly emphases. We know only what the author wants us to know and that is a figure of Boaz who reacts and responds rather than schemes and seduces. Furthermore, when we supply motive and additional backstory to the characters we are creating a kind of fan fiction, rooted more in our own interests and imagination than that of the original author.

[Ruth does present all sorts of questions that we cannot answer, but for which we would like answers, such as why Ruth and Orpah made different decisions.]

I recognize the irony of this paper. In the first portion I have argued, as have others, against many traditional commentators that the book of Ruth presents Boaz as a rather marginal figure, one who is reactionary and lacking in initiative. Yet in the second portion I am arguing against those who seek to further marginalize Boaz. One might argue that I am guilty of just the sort of rereading and recreation of Boaz as I have accused of others. Of course I think that I am not and what I am trying to argue for is a kind of p’shat, a simple reading of the text. Is such a reading ever truly possible? Perhaps not, but some readings are certainly more likely than others.

Bibliography

Beattie, Derek RG. “The Targum Ruth: A Preliminary Edition”. Page 231-290 in Targum and Scripture: Studies in Aramaic Translations and Interpretations in Memory of Ernest G. Clarke. Edited by Paul VM Flesher. SAIS. Leiden: Brill, 2002.

Beattie, D R G. Jewish Exegesis of the Book of Ruth. Sheffield: Sheffield University, 1977.

Beattie, D R G, McIvor, J Stanley, and McIvor, J S. The Targum of Ruth; The Targum of Chronicles; The Aramaic Bible. Collegeville: Liturgical, 1994.

Berger, Yitzhak. “Ruth and the David—Bathsheba Story: Allusions and Contrasts”. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 33, no. 4 (2009): 433-452. http://jot.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/33/4/433.

Bernstein, Moshe J. “Two Multivalent Readings in the Ruth Narrative”. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 16, no. 50 (1991): 15-26. http://jot.sagepub.com/cgi/content/short/16/50/15.

Brady, Christian MM. The Rabbinic Targum of Lamentations: Vindicating God. 3. Studies in the Aramaic Interpretation of Scripture. Leiden: Brill, 2003.

Bush, Frederic William. Ruth, Esther. Waco, Tex.: Word Books, 1996.

Campbell, Edward F. Ruth Anchor Bible. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1975.

Campbell, Edward F. Ruth A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. New York: The Anchor Bible; Doubleday, 1975.

Carmichael, Calum M. “A Ceremonial Crux: Removing a Man’ s Sandal as a Female Gesture of Contempt”. Journal of Biblical Literature 96, no. 3 (1977). The Society of Biblical Literature, 1977: 321-336.

Fewell, Danna N, and Gunn, David M. Compromising Redemption: Relating Characters in the Book of Ruth. Literary Currents in Biblical Interpretation. Louisville, Ky: Westminster John Knox, 1991.

Fewell, Danna Nolan, and Gunn, David M. “Boaz, Pillar of Society: Measures of Worth in the Book of Ruth”. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 14, no. 45 (1989): 45-59. http://jot.sagepub.com/cgi/content/short/14/45/45.

Hayward, Robert. Divine Name and Presence: the Memra. Totowa, N.J.: Allanheld, 1981.

Hubbard, R L. The Book of Ruth. Eerdmans Pub Co, 1989.

LaCocque, André. Ruth : a continental commentary. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2004.

Linafelt, T. “Narrative and Poetic Art in the Book of Ruth”. Interpretation 64, no. 2 (2010). Union Theological Seminary and Presbyterian School of Christian Education, 2010: 117-129.

Linafelt, Tod et al. Ruth and Esther. Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press, 1999.

Meyers, Carol. “”Women of the Neighborhood” (Ruth 4.17): Informal Female Networks in Ancient Israel”. Page 110-129 in Ruth and Esther: a feminist companion to the Bible. Sheffield Academic Press, 1999.

Nielsen, Kirsten. Ruth: A CommentaryThe Old Testament Library. Westminster John Knox Press, 1997.

Sasson, Jack M. “The Issue of Ge’ ullah in Ruth”. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 5 (1978): 52-64.

Schramm, G M. “Ruth, Tamar and Levirate Marriage”. Studies in Near Eastern culture and history: in memory of Ernest T. Abdel-Massih (1990). Univ of Michigan Center for Middle, 1990: 191.

Trible, P. “A Human Comedy: The Book of Ruth”. Page 161-190 in God and the Rhetoric of Sexuality. Nashville: Abingdon, 1982.

Wolde, Ellen van. “Texts in Dialogue with Texts: Intertextuality in the Ruth and Tamar Narratives”. Biblical Interpretation 5 (1997): 1-28.

3 thoughts on “Boaz: Centrally Marginalized”

A tedious but helpful and even necessary re-examination of the text. Thanks!