This is an entry in the “Acrostic Contemplations.”

Heresy is “a belief contrary to orthodox religious teachings or doctrine.” That is the general definition, but it is too broad to simply say “a belief contrary to orthodox religious teachings” since everyone at some point, even the most devout, hold various and varying beliefs. Heresy is an action, it is the promulgation of a teaching contrary to orthodoxy. That also means, and this is often overlooked, that heresy requires orthodoxy. Paradoxically, it also requires that the one being accused of heresy in some way is convinced that they are not heretical because otherwise they would simply leave that faith tradition.

My atheist colleague, for example, who believes that there was a guy named Joshua upon whom all of this Jesus stuff was based but rejects the notion that he was anything more than human, performed miracles, or rose from the dead, is not being heretical in those beliefs or in teaching them because he makes no claims to being a Christian. He is not a part of any Christian faith community so while he holds and perhaps even teaches views counter to that faith, he is not a heretic.

If, on the other hand, he were someone who was an ordained priest and bishop of a Christian church that affirmed the historical Christian faith, who affirmed in his baptismal vows and in daily recitation of the Creed that he believes that Jesus Christ “on the third day he rose again, ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of the Father,” but then asserts that the resurrection “does not mean that it was the physical resuscitation of Jesus’ deceased body back into human history,” that person is a heretic. That is not a judgment, it is a factual statement. It is also a fact, so I am told, that he was a lovely and gracious person. But that person was a heretic because he actively taught a belief directly contradicting the vows that he took at baptism, affirmed at ordinations as a deacon, priest, and bishop and then, from a position of power and authority, taught such views. Yet he never saw himself as a heretic, but rather a reformer.

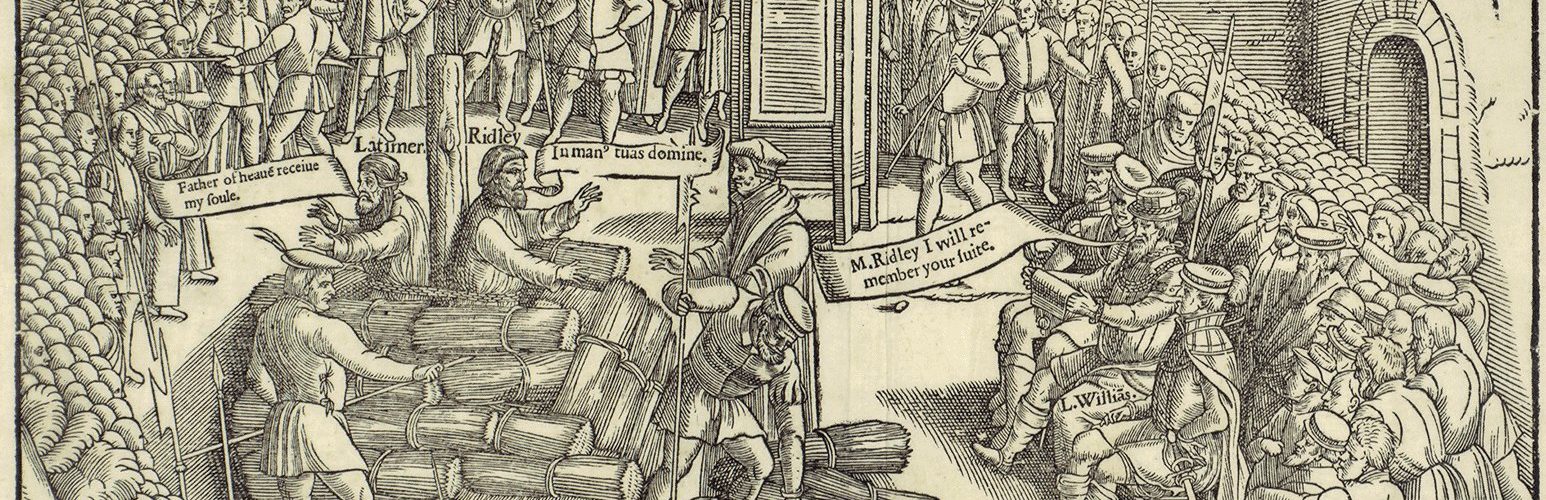

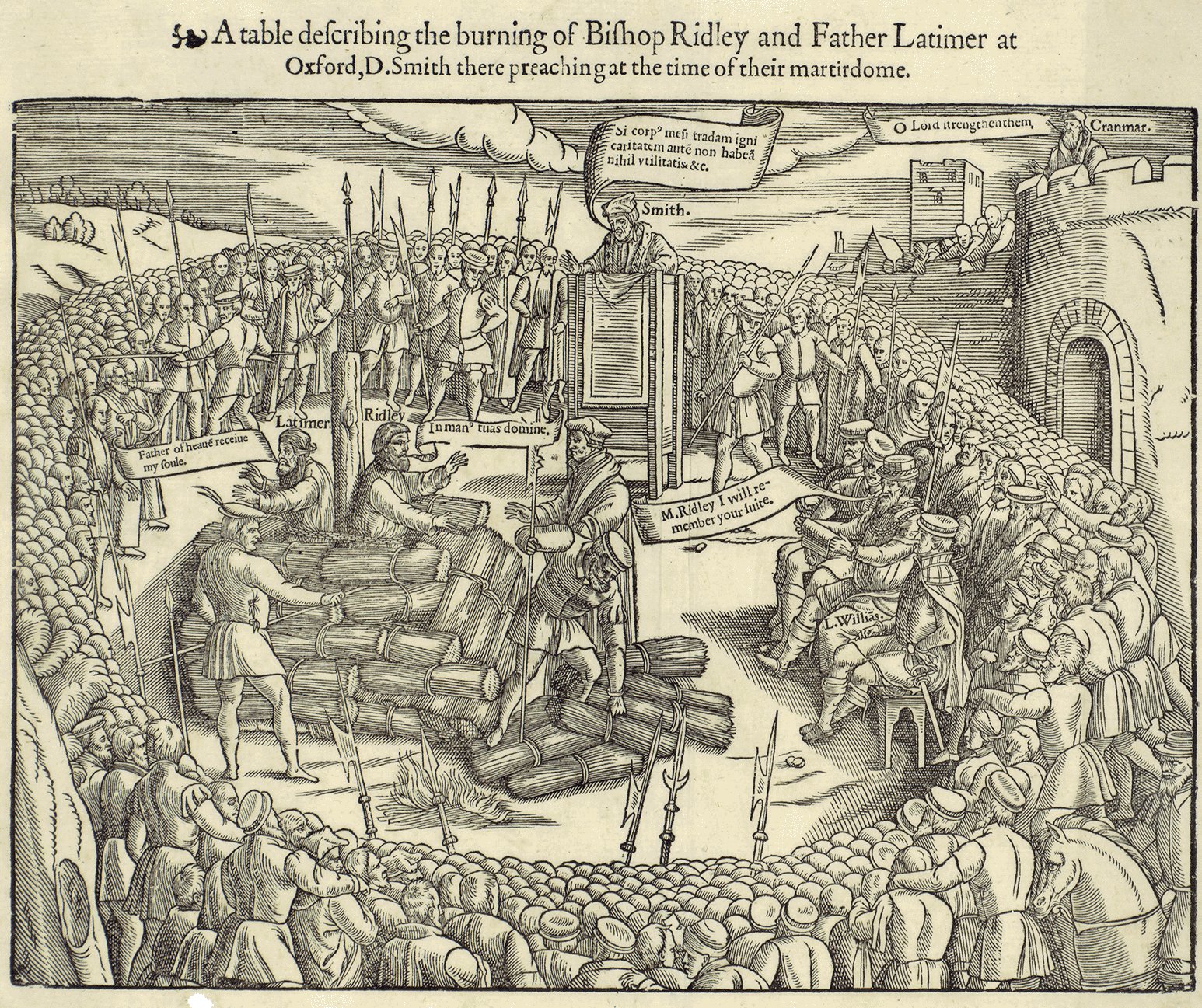

Historically in western Christianity, if someone was convicted of heresy they were executed because the church and the state were one and the state was responsible for upholding orthodoxy, often at the edge of a sword or the tip of a match. Often conviction was unnecessary. It is true for other religions in other countries today. Yet today, for Christianity in the United States and Europe, teaching counter to orthodoxy no longer carries a death penalty, at least not directly. It may, however, result in scurrilous attacks online and it might get you a book contract or at least a popular blog.

Is it still possible for one to be a “heretic” in our western Christian world today? The example above, at least in that church, suggests that there is no longer an “orthodoxy” against which a position can be considered heretical. On the other hand, there still exist many in the United States who hold so strongly to their orthodoxy that they virtually martyr women and men daily. There is a reason it is called “flaming.” Social media is the public square and tweets are the stones. Who stands by holding their cloaks?

Heresy cannot exist without orthodoxy and orthodoxy necessitates heresy. But when does heresy become reformation? Is it possible for a community of faith to hold to orthodoxy and not persecute the heretic? Is orthodoxy now a kind of heresy against the prevailing views of the day?

And who today is gracious and faithful enough to say, “Lord, do not hold this sin against them”?