This is an entry in the “Acrostic Contemplations.”

Then he said, “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.”

Memory is a fraught and fickle thing. What may seem certain and fixed in our minds as fact may be, to another rememberer, something entirely different. Something we may desperately want to remember, we find unable to dredge up from the depths, or goes flitting past the corner of our consciousness, a blur of color or scent or sound and no more. Was it real? Was it only real to me?

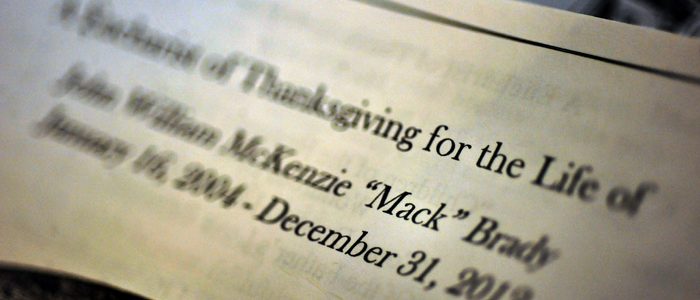

It was only a few weeks after Mack died that I had more than one panicky moment when I felt like I could not remember him, his voice, his face, all seemed to be receding rapidly, taking him even farther from me. To this day, when I want to conjure up his image in my mind, there are one of two moments I focus upon, iconic bits of phrase, gait, or look that will bring his presence to me. While I am confident of the resurrection, for the time being, he lives in our memories and that will have to do.

We shape memory, we preserve, protect, and create memories. How we do so is vitally important. After coming into his and his brother’s room, taking a peak at his sleeping boys, Frederick Buechner’s father took his own life. That memory flows through all of Buechner’s life and work. How could it not? The night that Mack died, Elizabeth and I were keenly aware that the way in which we grieved and mourned would shape our daughter’s life forever; Mack’s buddies’ too. We could not erase or remove the deep loss, we would not want to, but we could shape and direct in what we prayed would allow our loss to be…not redeemed, but made manageable. We can’t stop the crashing of the waves, but a surfer can ride and carve through the powerful water to create an experience that is affirming rather than devastating.

A key piece for us was creating the Mack Brady Fund for PSU Goalkeepers and the annual Clinic, where little kids come to learn soccer and hear of Mack’s passion for goalkeeping. His buddies who he played soccer with were ready to quit their sport because it reminded them that their ‘keeper wasn’t there anymore. The coaches and players at Penn State and from the MLS allowed them not only to continue to play, but to remember their friend and to celebrate him, even as they mourned. Now, each year, more than 100 young players, most of whom were not even alive ten years ago, come to the clinic to learn how to play soccer, to be a goalie, and get to know Mack and his love of the game and his position.

“Do this in remembrance of me.”

When we talk about our memories, we usually mean some moment or thought that occurred to us, that we draw up from our mental storage. Yet memory does not always occur in isolation, the making or the recollection. My memory of my own son is now richer and fuller because others have shared their own memories of him with me.

As Community, we reflect and remember major moments and they are shared down through the generations. In Exodus 12 God directs Moses and Aaron in how to frame the memories of God’s deliverance of his people from slavery in Egypt. The images, motifs, and themes echo throughout Scripture and history. Passover is commemorated by millions of Jews every year, around the world, each community in its own way and each year with its own slightly new, inflected meaning. New persecutions, pogroms, and plagues become embedded in the collective remembrance of the suffering of God’s people and their deliverance.

At the time of Passover, Jesus took those images, shaped and transformed them, placed his impending death into that framework, and commanded his disciples, “Do this in remembrance of me.” When Christians today celebrate the Eucharist, whatever the day of the year, “we remember his death, we proclaim his resurrection, we await his coming in glory.” We did not see it directly, yet we remember. It is our shared remembrance that has been handed down, transmitted and transformed without transgressing the truth of the memory.

The memory is mine. The memory is ours. The remembrance is holy.