From last Sunday. As with most sermons, I wrote sparingly and then in the preaching the sermon expands, but I think this captures my primary thoughts.

Proper 5, Year C, RCL

1 Kings 17:17-24

Luke 7:11-17

The Widows’ Sons – Why Not Mine?

When I came back to services one of the things I promised myself was that I would not bring our personal loss into every sermon. Our recent readings, particularly today’s make it extremely difficult to keep that promise. In both readings we find the son of a widow being resuscitated, brought back to life. God intervened to bring life where they believed was only death.

When I came back to services one of the things I promised myself was that I would not bring our personal loss into every sermon. Our recent readings, particularly today’s make it extremely difficult to keep that promise. In both readings we find the son of a widow being resuscitated, brought back to life. God intervened to bring life where they believed was only death.

You will notice I did not say “resurrected.” It is a technical difference, but an important one. Both of these men came back from being dead, but unlike the risen Christ who ascended into heaven and did not die again, these men, like Lazarus, lived again but only for a time.

The widow of Zarephath accurately states the cries of so many of us when we feel like we have given everything to God, suffered all we can bear, and then something worse happens.

“What have you against me, O man of God? You have come to me to bring my sin to remembrance, and to cause the death of my son!”

Just when it feels like we have it understood, when we are being faithful to God and things are beginning to work out (remember, the widow was near death when the prophet showed up and said, “feed me” and when she did so, in faith, they had enough to survive), things come crashing down.

Truth: This fall was incredibly difficult for me. I was wrestling with major issues in three areas of my life, but by the middle of December things had resolved themselves. I said to Elizabeth on Christmas Eve, as we sat wrapping presents for the kids who were asleep upstairs. “I feel so relieved that everything has begun to sort itself out. All is well and that makes me nervous about what the New Year will bring.” One week later Mack was dead.

I understand the Widow’s cry. We all do; how much more can you ask of us God?

But when I read these passages and ask, “why were these two sons saved” the answer is actually fairly obvious and is stated in each passage. They were saved in order to demonstrate that the one healing was truly from God. The widow of Zarephath announces, “Now I know that you are a man of God, and that the word of the LORD in your mouth is truth.” After Jesus resuscitated the boy, the people of Nain “glorified God, saying, ‘A great prophet has risen among us!’ and ‘God has looked favorably on his people!’”

So we have two questions we can ask of such circumstances in our lives and of such passages in the Bible. In the first case, we reasonably ask, “how could this happen?” We want to know what possible reason there could be for a widow, or anyone, to lose their child. And when we read such passages as these, where God intervenes and brings someone back from death, we ask, “why were they saved and not others?”

The latter question is, I think, the one worth posing because the former is sadly obvious.

Our children die because that is the natural and normal order of this world. Illness and accidents, evil people and thoughtlessness are all sadly part of this life, it is, by definition, ordinary. What is extraordinary is when miracles occur, when God intervenes.

Why sometimes and not others? It is not easy to say, but in our readings tonight we know that it is so that the messengers of God would be known and respected. The miracle confirms their message and mission.

I’m a preacher, I have sought to be a messenger of God, so why not Mack? Why not save him so that I could declare of God’s grace and salvation?

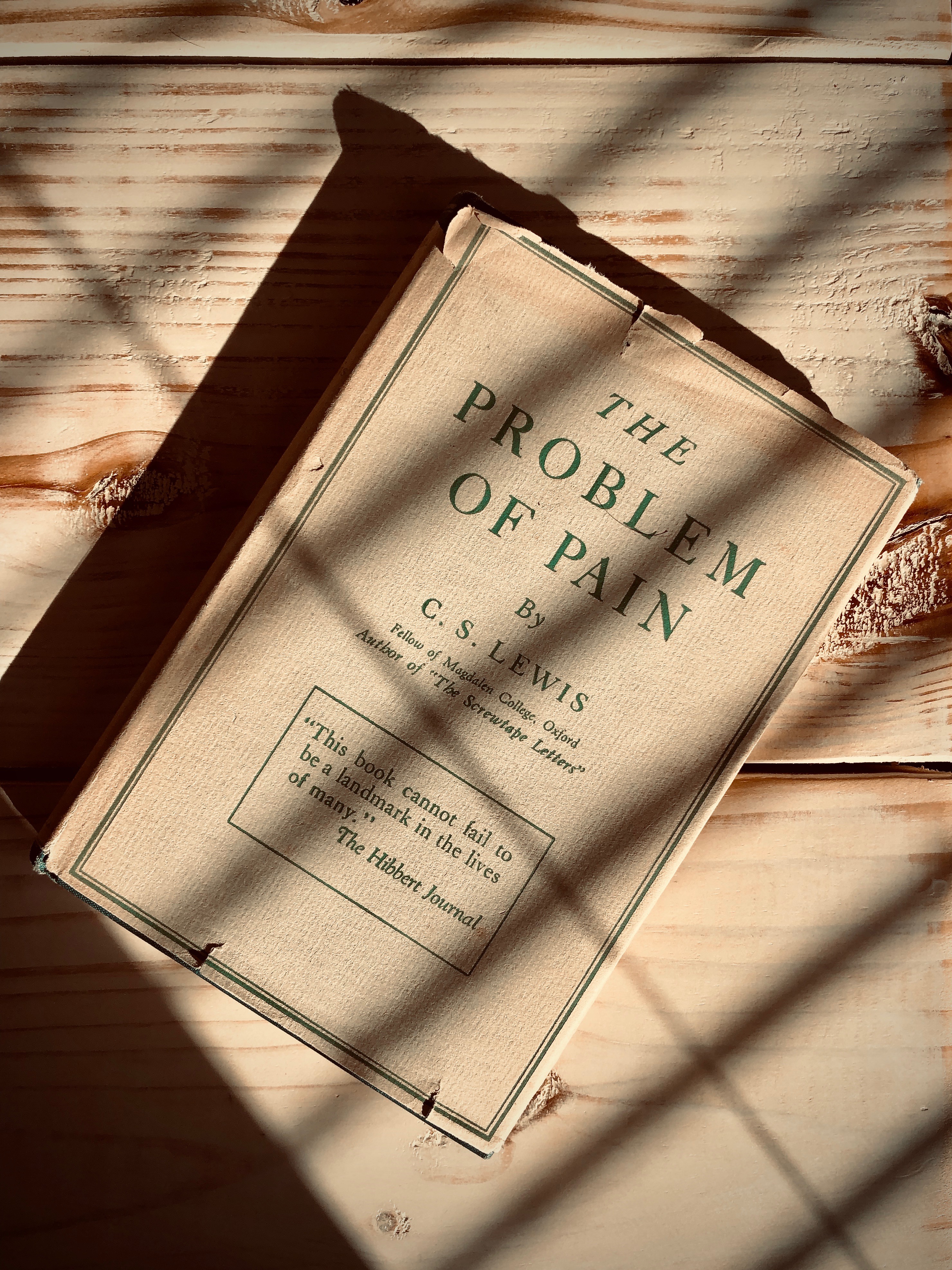

I don’t know. Neither does church historian Jerry Sittser who lost his mother, wife, and child in a car accident. Nor does theologian Nicholas Wolterstorf who lost his son in a mountain climbing accident. Nor do the multitude of faithful who have lost their loved ones, there was no miracle, no resuscitation, no second chance. I cannot say why not our children.

Perhaps it is so that we might speak for God not into the extraordinary, but into the ordinary, to address the real life experience of the vast majority of us, an experience that all too often includes death.

Yesterday at the diocesan convention someone thanked me for writing about Mack’s death and my own struggles and questions. He said that he especially appreciated my saying that his death, like all deaths, is the results of our living in a broken world. He said, “I had not really thought about the world in this way.” Perhaps it is because I have spent so much of my adult life studying the Old Testament, but to me, this is the only conclusion we can come to after reading Genesis three. This world was created to be perfect, but the exercise of our free will has broken it. The ordinary, real life that we live is enduring those scars and fractures.

Over 15 years ago I was on an email listserv of Christians from Cornell. There was one person who argued that Christians should only ever die of old age (or martyrdom or accident); never from illness. Our faith should heal us, he argued. My son, according to his argument, died because the prayers of my wife and I were ineffectual. But I would point out that we know Jesus didn’t heal every person who was ill, he didn’t resuscitate from the dead the many who called him Christ, even those who died before his own crucifixion.

Why? Because although there were extraordinary moments when God’s glory had to be exhibited there was also the normal business of life and death that would continue after his work on earth had been done. We continue to live in this real, physical, broken world. And it is in this world that we find grace.

Grace is not only God’s forgiveness of our sins, even when we do not merit forgiveness, but it is also the comfort and love sent from God to endure through the unendurable. How are we to endure it? In the knowledge that in God’s grace we have been forgiven and so this death is not the final death. In the knowledge that Mack is healthy and well and that we mourn, not for him, but for our dreams of the future we had hoped for with him, in this world. We rejoice, however, in the grace and knowledge that we have an eternity to be with him, with one another, and with God, through the resurrection of the one whose death brings us eternal life.

We don’t look for the resuscitation of the dead; we await the resurrection. ✠

6 thoughts on “The Widows’ Sons (or, Why not mine?)”

But I don’ want to deal with the ordinary…so well done Christian. You have inspired and enabled me to see the beauty and power and most especially the need and presence of grace in the ordinary which can make such extra-ordinary demands of us.

I agree Tim. I don’t want to either. That is the hardest part right now. Just getting on with life, with the quotidian.

I love your heart, Chris. So well said, and so real.

Miracles are, I think by definition, mysterious, and shall ever remain so. I think you’re absolutely correct to conclude that we believers suffer the same exposure to sickness and loss that everyone else in the world does–though we are comforted with a hope that no one in the world but us has. And while I do believe that God’s hand still moves to heal today, one has to point out, as you did, that not only did Jesus not heal everyone–even those who knew him– but also that sometimes he *couldn’t* heal them. It’s a seemingly tidy “scriptural” argument to lay such failure to heal on the lack of faith of the supplicant, except that doesn’t work in Jesus’ case.

“I don’t know” is the only honest and correct answer to the question of why He does or doesn’t intervene in any given circumstance, but the possibility I’ve been chewing on lately is that perhaps, sometimes, he can’t. Not that he’s incapable, but that there may be things about the structure of the created universe and the way things work, and the way God interacts with it and brings about his plan in the overall sense, that mean he has to not intervene in some cases, even when He wants to. And maybe it has to do with our choices, or someone else’s choice, or some spiritual battle of which we are unaware. Unless God tells us, we really don’t know.

Thank you Dan. I appreciate and agree with your ruminations and I cannot deny that lack of faith is one aspect of such impediments. But it leaves open the question, as I have tried to point out, what about when there is faith but no healing?

Of course the Gospel passage for last Sunday is just three short chapters away from Luke 4:

I was going to work this into the sermon, but didn’t have time. Jesus himself is pointing out this issue: many of God’s faithful were suffering with the famine and no doubt died as a result, but not only did Elijah (God) not provide for them all, but those he did provide for were not even Israelites! Ditto for Naaman. The closest we can come to answer in this passage (I think) is Jesus’ statement that the “no prophet is accepted in the prophet’s hometown.” That is usually viewed as their lack of faith in him (the verse immediately preceding has the people astonished by his exegesis saying, “Isn’t this Joseph’s boy?!”) and I think that is part of the equation but it cannot be all of it.

I am not sure I would be ready to say that this is due to God’s inability (given structures or what have you) to intervene. In fact, the other main point I was not able to put into the sermon was the challenge of the logical problem of evil and Plantinga’s response to it. As I have said elsewhere, I think ultimately our being given free will is the root of our situation.

The fact that God will at times intervene is not to be understood, however, that God will always intervene. I think that is where we find ourselves in a quandary and it is understandable, reading the Bible can give us that impression. For example, when reading Genesis one could get the impression that God was always hanging out with Abraham and talking with him. Yet when you actually look closely you realize even Genesis only reports a few engagements between them and those were separated by decades. Similarly, if we are reading the Gospels and Acts in isolation we can get the impressions that miracles happen all the time and every where. But that isn’t really the case, even in those texts and the events they describe.

As you put it so well, “miracles are, by definition, mysterious.” They are also not the “ordinary,” by definition. And while thankfully the extraordinary breaks into our lives, we mostly live “ordinary” lives and even in those times we have to recognize and accept Grace.

Loved the last two paragraphs.