Several years ago I heard an excellent lecture by Jonathan Culler about the concept of omniscient narrators. His talk really was very good, sadly he prefaced his talk with needless attacks on anyone who believes in a god or religion. I have written about that before, but never commented on the substance of his lecture before. I do not remember the details, but the main gist was that there really is no such thing as an “omniscient narrator” (ON). That is to say, even when an author is present us with the typical ON that we all learned about in 7th grade English, the narrator never really does reveal everything that s/he ostensibly knows. Instead the narrator may tell us what our main protagonist thinks and perhaps may shift to another character and reveal their thoughts for a time, but it is practicably impossible for the narrator to exhibit complete omniscience, even if we might assume that the author him or herself did know exactly what each character was thinking, doing, etc. This was the “no duh” aspect of Culler’s lecture. Of course what he said was patently obvious once one bothered to take note of it.

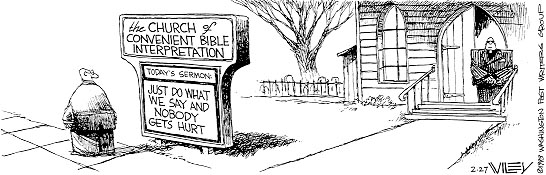

All of this is, in some ways, just an effort on my part to have a clever title for this post, but I have often thought about Culler’s comments and what they mean for authors and readers alike. I do think that such musings can be useful when we consider scripture. Particularly for those working within a faith framework where God is considered the “author” of not only the Bible but life itself. Certainly God is considered omniscient, but we do not, in fact, find any of our biblical narratives exhibiting what we would describe as an omniscient narrator. (If I am wrong, please feel free to correct me.) This is, of course, due to culture and context. Every genre and literary form owes its nature and character to the community within which it grows and it serves to remind us just how different the biblical narrative is from what we might write today.

17 thoughts on “The Omniscient Narrator”

Thanks for the report on Culler. I’ve gotten a lot out of his “literary theory: a very short introduction.”

For my part, I like to reflect on what this selectivity implies for the narrator’s “reliability.” Since the narrator doesn’t tell us all she knows, that means we cannot rely on her to tell us everything that *we* habitually think important about events. This isn’t new either: Robert Alter, Meir Sternberg, and others have talked about it. For me, it’s just one more helpful avenue toward the notion that texts want to provoke certain questions while discouraging others.

Interesting thoughts. The connection between selectivity and bias (in the negative sense) is a real issue, of course. Selectivity also is what gives us point of view, however, and the story that the author wants to tell, so I’d be careful to separate “selectivity” from the literary sense of “reliability” and “unreliability.”

I understand reliability in narration as having to do with the trustworthiness and accuracy of the narrator, rather than the narrator’s ability to read the mind of the reader, or a responsibility that the narrator must tell us everything that could possibly be told. Needless to say, those would be unrealistic expectations for the reader to place upon the writer.

I (usually) assume when reading that I am able to place a significant measure of confidence or trust in the writer, as radical skepticism can be paralyzing. When evidence leads us to suspect that the author is trying to trick or lie to us — rather than just tell her story the way she wants to — then we should talk about questioning her reliability.

The question is whether access to the thought of any character, and that of God, entails an omniscient narrator. If so, there are omniscient narrators in the Bible. As Brooke seems to know, there is a debate about that and two players in the discussion are Sternberg and Culler.

I confess I have not paid that much attention to this debate. What passages would you consider as those with an “omniscient narrator”?

Esther is a good example of an omniscient 3rd-person narrator. We read the thoughts or feelings of Esther (4:4), Haman (3:5-6; 5:9-10, 14; 6:6), and even Xerxes’ would-be assassins (2:21). Hmmm. Interesting how much we see of Haman’s internal process.

Ah! Very good suggestion (and it should have occurred to me immediately). Now, considering Esther is often cited as one of the first “novellas” (a title I have heard others give to the Joseph narrative, I will have to look at that story again now that I think about it) perhaps this becomes a criteria for categorizing some of the biblical narratives. Again, I sense I am very late to this party….

What’s interesting is how many examples of apparent “omniscience,” could also be interpreted in other ways. Is the mention of Jesus’ astonishment in Matthew 8:10, for example, omniscient narration, or an observed fact (Jesus perhaps saying that he was astonished, prior to the “Verily”), or an interpretation by a witness to the discussion, or a report of what Jesus later told to someone?

There’s a difference in certainty between my observation of how someone feels and my actual knowledge of how they feel. And we would write these differently. “Chris looked delighted,” versus “Chris was delighted.”

In the Gospels I would think John would be ripe for this. I do not have time to find the exact reference but I recall several points where John tells us why (the motivation) Jesus did something. This certainly implies, if not assumes, an ON who knows what the subject is thinking.

John 2:24 and 25 would be one example. 13:11; 13:21; 18:4.

If we only saw into one character (Jesus), we would call it 3rd-person “limited” rather than omniscient narration. John 12:42-43 reveals others’ thoughts and motivation (unless this is opinion rather than omniscience).

Then there’s John 1:1-5…. Is this omniscience, or revelation, or reported speech, or…?

What a difference it makes, whether we start from an assumption that the author is making up a story or from an assumption that the author is reporting what he believes to be true — perhaps from information shared by others. If the latter, the author would reject the “omniscient” label and point of view.

And of course your bring into the discussion a point which is moot in relationship to other literature but is valid for many with regards to the Bible, that is the possibility of revelation. It is not an “omniscient” narrator, 3rd-person limited, or anything else, it is a revelation thus the narration is informed/silent only in so far as the Revelator has chosen.

But that is a very different approach to reading the Bible…

In practice, however, I am not sure that we make such distinctions.

“How did the dean respond to your offer to teach an honors class?”

“He was delighted.”

Presumably the dean not only was delighted but exhibited his delight. But of course he could also be hiding his uncertainty yet wanted the faculty member to believe that he was pleased with the offer.

In The Poetics of Biblical Narrative, Meir Sternberg argues for the view that biblical narrators are omniscient. Here’s a quote: “Given the biblical narrator’s access to privileged knowledge – the distant past, private scenes, the thoughts of the dramatis personae, from God down – he must speak from an omniscient position.” (12). Limited narration, with a first-person (as opposed to anonymous omniscience), is, he notes, a feature of relatively late writings: he mentions apocryphal and gospel literature – but this is misleading. One might mention already Amos, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Habakkuk, Qohelet and Daniel).

Still, Sternberg concentrates on the Primary History, and in particular, on the Patriarchal Narratives. There his case is relatively strong.

Culler in the Literary in Theory problematizes Sternberg’s categories (pp. 186-190).

Thanks John! I will have to find time to peruse this. I have not read Culler’s work there, but I find it interesting that Culler should engage with Sternberg’s work on the Bible (assuming that is what is going on) since Culler argued in person that teaching religion in general and the Bible in particular should not be taught since all religion is the source of so much evil, ignorance, and suffering.

I don’t have easy access from home to Meir Sternberg, “Omniscience in Narrative Construction: Old Challenges and New,” Poetics Today 28 (2007) 683-794. That’s a promising title.

John: You might be able to find the document at this link:

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.128.3878&rep=rep1&type=pdf

If that does not work for you, I would recommend attempting http://scholar.google.com — I bet it will have a workable link for you (if not email me, and I will send you the document you. You can reach me at Penn State with spb7 )

I’ve just stumbled across your comments on omniscience. I see you’ve received some excellent feedback. And obviously I am late to your party.

I will say that Sternberg taught me a lot when he suggested that omniscient narrators vary in the degree to which they are omni-communicative.

I did have an interesting exchange with him in NARRATIVE, responding as I did to a revision of the lecture you ‘ve mentioned and his responding to me, conceding me a few of my points, at any rate.

http://muse.jhu.edu/login?uri=/journals/narrative/v014/14.3olson.html

http://muse.jhu.edu/login?uri=/journals/narrative/v014/14.3culler.html

Perhaps your interest in omniscience is long past, but just in case I thought I’d put in my nickel’s worth.

Barb Olson