This brief post began as a response to a comment on my earlier post “Age in the Book of Ruth and a Proxy Marriage?” The commentator very simply stated that the marriage between Ruth and Boaz was because “a baby needed to be born to preserve the line of Naomi’s husband.” It was suggested (stated really) that I do not understand Jewish law. Now, I do not pretend to be an expert in all things halakhic, but I do know that with respect to the Book of Ruth the legal issues are quite complicated. Here I will simply outline the primary issues and offer a brief bibliography.

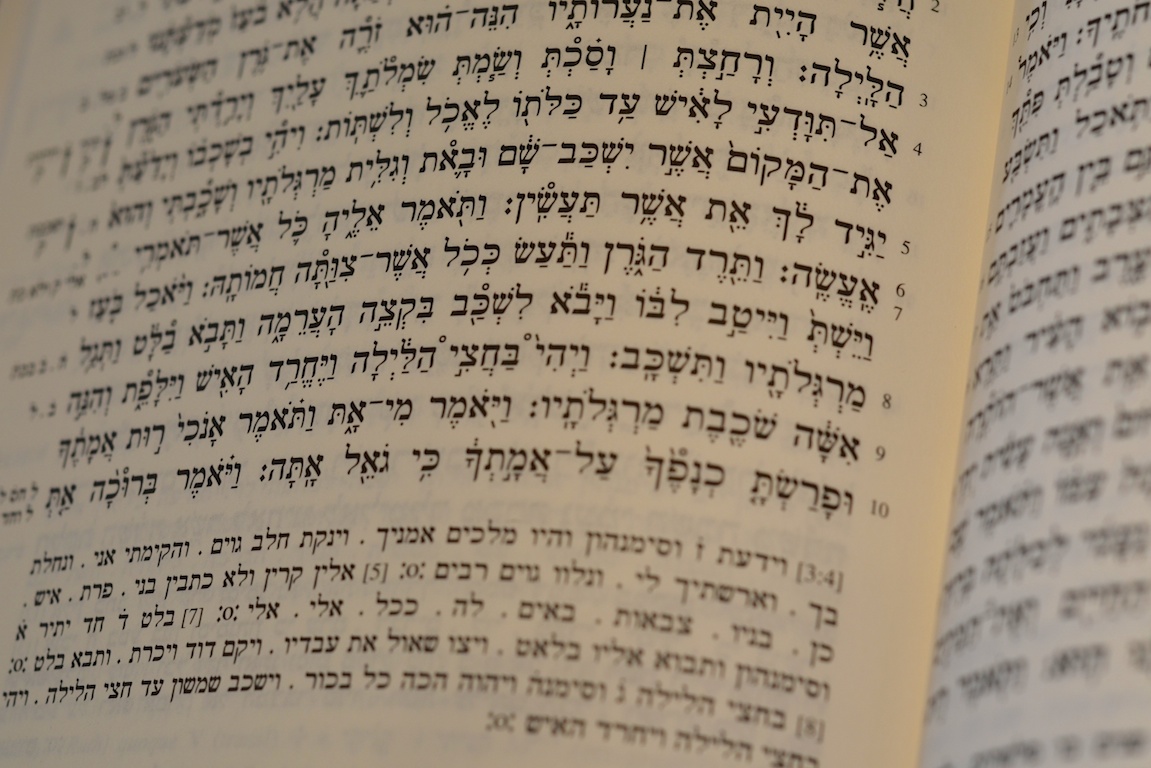

First, we should make a distinction between “Jewish Law” (“halakhah”) and Biblical Law. The latter, obviously, refers to the Law found in the Bible, in this case the relevant passages are Deut. 25:5-10 and Lev. 25:24-34. The former refers to Jewish Law the post-dates the Bible, such as the Mishnah and Talmud, specifically, the tractate Yevamot. Now, in the case of the Book of Ruth, there is considerable debate about what, legally, is going on with Boaz and Naomi/Ruth. A quick perusal of a critical commentary will bring this out, but I will summarize here. [mfn]See, e.g., Nielsen, The Book of Ruth, pp. 74-6 and Campbell, Ruth (Anchor Bible Commentary), pp. 132-38.[/mfn]

Naomi says Boaz is a האיש משאל, a “kinsman redeemer” (Ruth 2:20). The relevant biblical law here is Lev. 25:24-34. The issue is that the property should remain within the family. This seems to be the legal issue at hand. Presumably, but not certainly, there was property that Elimelech owned which Naomi could sell to provide for their needs. Boaz is a near kinsman and would have the first (or as we find out, the second) right of refusal. So why does he marry Ruth?

At the threshing floor, It would seem that Deut. 25:5-10 is being invoked when Ruth says, “I am Ruth, your servant; spread your cloak over your servant, for you are next-of-kin.” This is what is known as “levirate marriage.” That term is from Latin, “levir” for “husband’s brother.”

Deut. 25:5 When brothers reside together, and one of them dies and has no son, the wife of the deceased shall not be married outside the family to a stranger. Her husband’s brother shall go in to her, taking her in marriage, and performing the duty of a husband’s brother to her, 6 and the firstborn whom she bears shall succeed to the name of the deceased brother, so that his name may not be blotted out of Israel.

And that is the difficulty, Boaz is NOT Elimelech’s brother. Boaz, nor “so-and-so,” was under any obligation to marry Naomi. And it would be Naomi, not Ruth who should be married anyway, but that is the least of the issues. The wife of the son would be reasonable to continue the lineage. The issue is that while biblical law obliges the near kinsman to “redeem” their property so that it stays within the clan, the obligation of marriage is reserved for the husband’s brother. So, Boaz has NO obligation to marry Ruth, according to the biblical law.

This is why the legal issues with the Book of Ruth are so perplexing. It is not in keeping with biblical law as preserved in the canonical texts. A few possibilities arise from that fact. Is the Book of Ruth reflecting the practice of local law at the time of writing? This would be distinct from the written law and, perhaps, even ignorant of it. Is the Book of Ruth thus descriptive of local practices and customs (e.g., the sandal issue) and Deuteronomy and Leviticus prescriptive? (The latter is certainly true. The legal texts represent how things ought to work, even if they never did work that way.) Or was the author of Ruth simply weaving the tale in such a way as to create audience interest and tension in the narrative?

So, it is not such a simple legal situation after all. And I have not even touched on the rabbinic halakhah in Babli Yevamot…

A brief bibliography

In addition to the usual commentaries, here are a few articles on the subject.

Anderson, A A. “The Marriage of Ruth.” Journal of Semitic Studies 23, no. 2 (1978): 171-183.

Bar-Ilan, Meir. “The Attitude toward Mamzerim in Jewish Society in Late Antiquity.” Jewish History 14, no. 2 (2000): pp. 125-170.

Baylis, Charles P. “Naomi in the Book of Ruth in Light of the Mosaic Covenant.” Bibliotheca sacra 161 (2004): 413-31.

Beattie, D R G. “The Book of Ruth as Evidence for Israelite Legal Practice.” Vetus Testamentum 24, no. 3 (1974): 251-267.

Beattie, D R G. “The Targum of Ruth: A Sectarian Composition?”. Journal of Jewish Studies 36, no. 2 (1985): 222-229.

Belkin, S. “Levirate and Agnate Marriage in Rabbinic and Cognate Literature.” Jewish Quarterly Review 60 (1970): 284-87, 321-22.

Berman, J. “Ancient hermeneutics and the legal structure of the book of ruth.” Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 119, no. 1 (2007): 22-38.

Berquist, Jon L. “Role Dedifferentiation in the Book of Ruth.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 18, no. 57 (1993): 23-37.

Braulik, Georg. “The Book of Ruth as Intra-Biblical Critique on the Deuteronomic Law.” Acta Theologica 19 (1999): 1-20.

Brenner, Athalya. “Naomi and Ruth.” Vetus Testamentum 33, no. 4 (1983): pp. 385-397.

Brenner, Athalya, A feminist companion to Ruth. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993.

Britt, Brian. “Death, Social Conflict, and the Barley Harvest in the Hebrew Bible.” Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 5 (2005).

Burrows, Millar. “The Marriage of Boaz and Ruth.” Journal of Biblical Literature 59 (1940): 445-54.

Burrows, Millar. “Levirate Marriage in Israel.” Journal of Biblical Literature 59, no. 1 (1940): 23-33.

Burrows, Millar. “The Ancient Oriental Background of Hebrew Levirate Marriage.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 77 (1940): 2-15.

Campbell, Edward F., Jr. “Ruth Revisited,” Pages 54-76 in On the Way to Nineveh. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1999.

Carmichael, Calum M. “A Ceremonial Crux: Removing a Man’s Sandal as a Female Gesture of Contempt.” Journal of Biblical Literature 96, no. 3 (1977): 321-336.

Carmichael, Calum M. “‘Treading’ in the Book of Ruth.” Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 92 (1980): 248-66.

Cohen, Shaye J D. “Can a Convert to Judaism have a Jewish Mother,” Pages 19-31 in Torah and Wisdom. New York: Shengold Pubns, 1992.

Davies, Eryl W. “Inheritance Rights and the Hebrew Levirate Marriage: Part 1.” Vetus Testamentum 31, no. 2 (1981): pp. 138-144.

Davies, Eryl W. “Inheritance Rights and the Hebrew Levirate Marriage: Part 2.” Vetus Testamentum 31, no. 3 (1981): pp. 257-268.

Davies, Eryl W. “Ruth 4:5 and the Duties of the go’el.” Vetus Testamentum 33 (1983): 231-234.

Derby, Josiah. “A Problem in the Book of Ruth.” The Jewish Bible Quarterly 22, no. 3 (1994): 178-85.

Dommershausen, Werner. “Leitwortstil in der Ruthrolle,” Pages 394-407 in Theologie im Wandel. Minich and Freiburg: Wewel, 1967.

Dyk, Janet W and Shadrac Keita. “The Scene at the Threshing Floor: Suggestive Readings and Intercultural Considerations on Ruth 3.” Bible Translator 57 (2006): 17-32.

Fisch, Harold. “Ruth and the Structure of Covenant History.” Vetus Testamentum 32, no. 4 (1982): 425-437.

Fischer, Irmtraud. “The Book of Ruth: A ‘Feminist’ Commentary to the Torah?,” Pages 24-49 in Ruth and Esther. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1999.

Friedman, Mordechai A. “Tamar, a Symbol of Life: The “Killer Wife” Superstition in the Bible and Jewish Tradition.” AJS Review 15, no. 1 (1990): 23-61.

Gordis, Robert. “Love, Marriage, and Business in the Book of Ruth,” Pages 241-64 in A Light Unto My Path: Old Testament Studies in Honor of Jacob M. Myers. Edited by R D Heim H. N. Bream, and C A Moore. Temple University Press, 1974.

Gosse, B. “Subversion de la législation du Pentateuque et symboliques respectives des lignées de David et de Saül dans les livres de Samuel et de Ruth.” Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 110, no. 1 (1998): 34-49.

Hendel, Russell J. “Ruth: The Legal Code for the Laws of Kindness.” Jewish Bible Quarterly 36 (2008): 254-260.

Leggett, D., The Levirate and Goel Institutions in the Old Testament with Special Attention to the Book of Ruth. Cherry Hill, N.J.: Mack, 1974.

Manor, D W. “A Brief History of Levirate Marriage as It Relates to the Bible.” Near Eastern Archaeological Society Bulletin (1984): 33-52.

Puukko, A. “Die Leviratsehe in den Altorientalischen Gesetzen.” Archiv Orientální 17 (1949): 296-99.

Richter, H F. “Zum Levirat im Buch Ruth.” Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 95 (1983): 123-126.

Sasson, Jack M. “The Issue of Ge’Ullah in rUth.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 3, no. 5 (2016): 52-64.

Schramm, G M. “Ruth, Tamar and Levirate Marriage.” Studies in Near Eastern culture and history: in memory of Ernest T. Abdel-Massih (1990): 191.

Weisberg, D E, Levirate marriage and the family in ancient Judaism. Brandeis Univ, 2009.

Wright, Jacob L. “Making a Name for Oneself: Martial Valor, Heroic Death, and Procreation in the Hebrew Bible.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 36, no. 2 (2011): 131-162.

4 thoughts on “Marriage and Redemption in the Book of Ruth”

Thank you for providing some background on this. I am planning to preach from Ruth 3-4 this Sunday (inspired partly by your work) and have never understood the legal issues. I never understood quite how Boaz would be a go’el, and especially don’t understand why So-and-So backs out in chapter 4 (and that’s even taking into account Rendsburg’s article on the verbs in 4:5, refers to Eblaite to explain that Boaz announces he has *already* acquired Ruth). Could you explain a little more “and it would be Naomi, not Ruth who should be married anyway”. Why? Ah… because Naomi is already a widow? Who stepped in (or should step in) to redeem her? Even after reading a couple commentaries I struggle to understand how Naomi might be the main character (begins and ends with Naomi, Ruth’s son somehow redeems Naomi). Todah.

Thanks Rick! Whether it should be Naomi or Ruth I suppose depends upon how one wants to understand the preservation of the name. Is it Elimelech’s name that is being preserved or Mahlon’s? It is Elimelech’s name that is repeated throughout the story (and it is only in 4:10 that we find out definitively that it is Mahlon Ruth married and not Chilion) and Boaz and So-and-So are described as being Elimelech’s near kin. Of course, that would also make them Mahlon’s near kin as well.

If we assume Levirate marriage (which this shouldn’t be since none of these men are Elimelech’s bother), then it would be Naomi, as the current, surviving wife who should be taken into the household “and the firstborn whom she bears shall succeed to the name of the deceased brother, so that his name may not be blotted out of Israel.”

Would could make the same argument again for Ruth, but then it would be to carry on Mahlon’s name, not Elimelech’s (even though in continuing his “name” the father’s name continues as well). The fact that we do, as you note, end with Naomi:

“17 The women of the neighborhood gave him a name, saying, “A son has been born to Naomi.” They named him Obed; he became the father of Jesse, the father of David.”

The real irony is that the name of Elimelech (and Mahlon) DO die out! The genealogy that follows does not list Elimelech or Mahlon, but Boaz as the father of Obed, the father of Jesse, the father of David.

Regarding main characters, I have argued that the author flows beautifully between Ruth AND Naomi as the main character. (See my brief “commentary” on this site.) Chapter 1 is Naomi, Chapter 2 is Ruth, Chapter 3 is Ruth following Naomi’s direction, and Chapter 4 is Boaz acting on their behalf.

Ugh what a mess. Thanks for the reply. Follow up question = What if Naomi is too advanced in years to have another child? Perhaps for practical reasons the only way she can be “redeemed” is through her daughter in law. The story leaves us with so many unanswered questions!

She is, perhaps, too old to have children (see Ruth 1:12-13) but Naomi and Boaz are likely similar age and older than Ruth. See my prior post.